Fire batons and acrobats along the first base line. Beauty queens on the mound. A fleet of motorcycles roaring across the infield. PA music cranked up to jet engine volume plus a live oompah band.

It must be baseball in Mazatlán

When I (Alex Thomas) first suggested researching Steve Dalkowski’s baseball career south of the border, it was actually a joke. I had spent a cold rainy week paging through musty archives in Connecticut and a scorching hot week up and down the central valley of California in pursuit of the Dalko story. Wouldn’t it be nice to spend a few days in a resort town on the Pacific coast of Mexico?

Though we knew Dalko had thrived with the Venados of Mazatlán, as far as my co-authors and I could tell, no one had ever conducted serious research there. Soon my wife – who came along to translate and help with research – and I were on the ground in Mexico, speeding from our beachfront hotel to the Venados ballpark via pulmonía, the overgrown golf carts that carry tourists to and fro.

We had no idea how vital to the story Dalkowski’s Mazatlán experience would turn out to be nor how much of an absolute hoot it is to experience baseball Mexican style.

The reason for our interest was that throughout his career, during the regular season Dalko struggled endlessly to control his historic fastball. When he was on his game, nobody could touch him. When he wasn’t, his heater was a hazard to umpires, reporters in the pressbox, and batters in the on-deck circle. He once even beaned a fan in line to buy a hot dog (the fan asked him to autograph the ball).

Yet when Dalko played winter ball in Mexico his control was significantly better. Though far from perfect, he was more consistent, relaxed, and dependable. Even near the end, as his American career disintegrated into a sad tale of missed opportunities and unfulfilled potential, he was throwing strikes and winning games before thousands of cheering fans in Mazatlán. His last season of pro ball was in Mexico. Far from being a disappointment, it was statistically one of his best.

Why was he such an improved performer in the Mexican leagues and such a basket case during the regular season?

The answer takes us back to fire batons and motorcycles. Baseball in Mexico was – and is – serious business but also serious fun. It’s one big party, long on enjoyment and short on tension and stress. Dalko evidently thrived on the party atmosphere of the stadium there, whereas the tension and stress he felt alone on the mound in America drained him of confidence and control.

As our story came together, it became increasingly obvious that a chief reason for Dalkowski’s control problem was nerves: when the going got tough, Dalko got the yips. Cool and deadly accurate warming up on the sidelines, he too often felt pressure during a game that ruined his performance.

This diagnosis came up time after time. Eddie Robinson, a spry ninety-six when Brian Vikander interviewed him for our book in 2017, is one of the few living former players who saw Dalko in action. He told us that on the sidelines Dalkowski’s control was consistently solid; alone on the mound, his confidence disappeared and the wildness took over. Oriole pitcher Jack Fisher agreed that after an inevitably impressive warmup, Dalkowski would get “anxious, overexcited, and nervous” during a game. Manager Clyde King, working with Dalko in 1962, commented to a reporter, “He tries too hard, and the harder he tries – when he’s conscious of the target – the wilder he gets.” (See the book for citations).

For Dalkowski, the lower-key attitude in Mazatlán was a perfect antidote for the yips.

Steve’s first year of winter ball was 1960-61. After the regular season ended following the World Series in October, he joined the annual migration of American professional baseball players to the Mexican League. There, where temperatures were warm and the atmosphere relaxed, they could maintain their competitive edge, work on their game, and earn good money in the off season. Sometimes major leaguers recovering from injury or needing special attention went to Mexico to escape the spotlight of the American press.

Steve played in the Sonora Winter League (later the Mexican Pacific League) for the Venados de Mazatlán, the “Deer of Mazatlán.” The city name means “place of the deer” in the native Indian language. Mazatlán in the 1960s was a relatively isolated resort on the Pacific coast of Mexico, north of the only other Mexican vacation spot on the Pacific in those years, the more famous and lively winter playground of Acapulco.

In September 1962 Steve signed a contract to play winter ball for the Orioles again, this time in Puerto Rico. The team announced his assignment on October 22. Plans changed, however, because Dalko began the winter season on the roster of the Cardenales de Lara in the Venezuela Western League. A likely reason for the change was that Earl Weaver was managing the Cardenales and, based on their outstanding success during the regular season, one or both of them wanted to keep working together.

Dalkowski pitched 38 innings over 10 games in Venezuela for a 3-3 record. On a percentage basis it was his best effort to date, the first where the losses didn’t outweigh the wins. He struck out 56 batters and walked 44 for an ERA of 5.21. In January he moved on to Puerto Rico where he played for the Indios de Mayaguez.

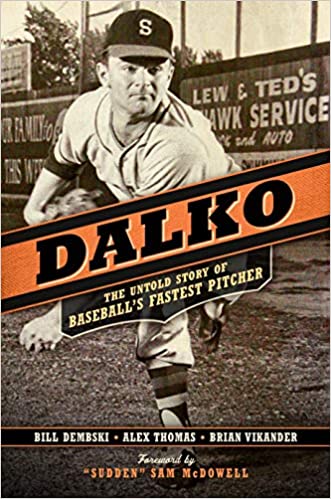

Steve returned to Maztlán after the 1965 Major League season. His highly anticipated Sonora Winter League debut that season was on October 12. It was the first time in league history that an American pitcher had received the honor of starting the season opener. Dalko, known as “El Velocista” to his Mexican fans, lost 5-2 in an exciting pitching duel that saw Dalkowski throw far more pitches than his rival Vicente Romo de Guaymas. Billed as “el lanzador más veloz de todos los tiempos” (the fastest pitcher of all time), Steve reportedly hurled the baseball at 108 miles per hour.

Seemingly on his last legs as a professional ball player, Steve Dalkowski was a genuine sports hero south of the border that year. Every day at the local stadium, a few minutes’ walk from the beach, fans could find a party, carnival, and baseball game all rolled into one. The locals loved baseball, and they loved El Velocista. Opposing teams came to town simply hoping to avoid a blanqueo (shutout) and their hitters approached the plate every time fearing another poncho (strikeout).

Eyewitness to History

Since my wife and I hadn’t been able to make any contacts with the Venados before we arrived in Mazatlán, we started from scratch. We walked up to the nearest entrance gate at the Estadio Teodoro Mariscal ballpark, which was locked but had a security officer standing nearby. We explained to him that along with seeing the Venados in action, we wanted to learn more about the history of the team and about a former American player in particular.

There are times when luck, fate, divine intervention, or whatever you want to call it reaches out and directs your path in a project like this. In that moment, we were directed to Omar Garzon. A handsome man with regal bearing and a black moustache, he reminded me of a 50s-era movie star. He embraced our project wholeheartedly, and from that moment on became our host, guide, and inside connection to everyone we met and everything we learned about Steve Dalkowski in Mazatlán.

Over the next several days, Omar introduced us to a host of gracious people who made our search for details about Dalko’s years in Mexico both a success and a delight.

Before game time that night, Omar escorted us to the broadcast booth to meet “Señor Beisbol,” José Ramón Flores, the Venados radio play-by-play commentator since 1993 and an expert in local baseball history. He shared his Mexican Pacific League stats with us, confirming the basic information we had about Dalkowski, and encouraged us in our efforts.

But the WOW moment with Sr. Flores came later in the game when he announced our project on the air and invited anyone who had seen Steve Dalkowski in action to call in. And someone did! A day or two later we spoke with Eduardo Jimenez who, as a thirteen-year-old boy, had seen Steve Dalkowski in full glory on the mound.

On Sunday, October 23, 1960, Dalkowski pitched a game that fans in Mazatlán still talk about. It was the second game of a doubleheader against the Ostioneros de Guaymas. Describing the game more than half a century later, Sr. Jimenez carried all the excitement and wonder of the moment in his voice. Mazatlán is in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. “If you don’t love baseball,” he declared, “you’re not a Sinaloan!”

The pitches were “fast, fast, fast,” he recalled, and sounded like the buzzing of a bee as they flew toward the mound. Steve “broke” batters like a cowboy breaking horses or burros, so fans called him “Burro Buster” along with his other nicknames. That afternoon young Eduardo and an astonished crowd watched as Dalkowski gave up a triple to the first batter, Gonzalo Villalobos, then retired 27 batters in a row. Sr. Jimenez was our eyewitness to history.

(Despite numerous eyewitness accounts of this game, including one by the father of the Venados’ TV play-by-play announcer, league records do not include statistics for Dalkowski in 1960. League reorganizations in 1959 and 1971, the Venados’ move to a new stadium in 1962, and the removal of all local newspaper archives to Mexico City about 600 miles away may help explain the missing information.)

Eduardo added colorful details that go beyond the stat sheets. He said Steve was a master on the mound. Fans loved his passion for the game, his intensity, and his protestations whenever he was relieved – he never wanted to leave the job undone. Teammates loved him because he was so kind and easygoing, always eager to help younger players improve their game. He would still lose control but he was able to regain it. Fans saw one catcher after another massaging his sore hand after a session behind the plate with Dalkowski.

Fiesta time!

As I quickly discovered, baseball in Mazatlán is part carnival, part birthday party, and part circus show with some baseball thrown in. And the best seats in the house are 200 pesos, less than ten dollars. Walking into the stadium, the assault on the senses is hard to describe. The PA music and announcer are at blast levels. They compete with commercials, announcements, and play-by-play coverage on the electronic scoreboard, plus a rowdy and enthusiastic live oompah band complete with tuba, a nod to the region’s German heritage.

Most amazing of all was the on-field entertainment between innings, which included live commercials for cars and motorcycles – complete with fleets of each on the infield, plus circus acrobats running along the baseline throwing fire batons into the air, beauty contestants posed on the mound, and raucous scoreboard videos of exuberant fans in the stands.

Children and families were everywhere, as were groups of teenage girls dressed to kill in their club-hopping outfits, older couples, school groups, dance squads, just about everything. Mazatlán fans love baseball, but they don’t take it too seriously.

Evidently, this party atmosphere and low-key attitude allowed Steve Dalkowski to relax on the mound and throw such consistently good innings in Mexico. With expectations low and the pressure off, Dalko could do his best work. The crazy environment meant Steve was not so much the center of attention and could just rare back and throw the baseball.

A Different World

Many years later, young American pitchers still play in Mazatlán and thrive on the lack of stress and the outpouring of local support from the fans.

Two American pitchers took time to visit with us and share their take on playing in Mexico. Mitch Lively, originally from Susanville, California, and Nick Struck, a native of Portland, Oregon, gave us a feel for baseball in Mazatlán. The level of play is high, players are genuine celebrities around town, and the stress factor is low.

As Nick explained, “In the States, when you’re in the minors nobody knows who you are. Here I’m standing by the side of the road waiting for a taxi and people going by say, ‘Hey, Struck!’ Everyone knows who you are. In restaurants people come up and ask for pictures. Down here it’s a different world.”

Scanning the field an hour before game time, Mitch said, “We’re not here just for the paycheck. Look at how many guys are out here early. Guys wanting to get better, guys wanting to be at the park, guys wanting to be with their friends.” He added, “Fans are so much more into the game and want to know who the players are. It’s like the big leagues in the States.”

During my first Venados game, I watched Mitch break the league record for successive wins with eight in a row, besting the mark set in 1948 by legendary Yankee hurler Whitey “Chairman of the Board” Ford. Several times that week I watched Nick stride to the mound in relief to unleash his 95+ mph heater as the sound system blasted “Fireball.”

The two of them agree that American pitchers have to gain the respect of the umpires. When a new norteamericano starts out, the strike zone seems compressed when compared to the zone for established pitchers. But over time, with a show of professionalism and patience, the newcomers earn their stripes. Lively and Struck take the party atmosphere and distractions of Mexican baseball in stride. If between innings there’s a Harley-Davidson promotion with a fleet of real motorcycles on the field, or a team of acrobats tossing fire batons along the first base line, it doesn’t matter to them. Their world is the game, the next pitch, the little circle of the catcher’s glove behind the plate.

Update: In 2020 Nick was pitching in Monterrey, Mexico, and Mitch was on the mound in Taiwan.

El Velocista

Though there was no PA music in Dalkowski’s day, an account from the newspaper El Regional of a game in Hermosillo on December 8, 1965, conveys some of the excitement Steve generated when he was on the mound. Under the headline that translates “The Sugarcaners Fall Before Steve Dalkowski” the paper recounts a 4-1 victory over the Cañeros. A crowd of more than 6,000 cheered El Velocista as he led the Venados to victory despite 10 walks in the game. It was no doubt a thrill for Steve to play in front of such a large and enthusiastic audience when in San Jose the crowds were often in the low hundreds. By the end of the season on January 16, 1966, Dalkowski was tied with pitcher José Peña for the most shutouts in the Sonora League.

Steve appeared in 20 games for Mazatlán that season with a 7-9 record. In 98 innings he allowed 41 runs on 72 hits with 85 strikeouts and 77 walks, for an ERA of 3.30. He threw five shutouts, all of them complete games. These are not the numbers of a baseball has-been. These are the numbers of a pitcher with tremendous talent and at least a few years of potential left. Given his impressive, albeit uneven, 1965 season in Mexico, it is clear that, far from being a baseball basket case hopelessly compromised by an elbow injury and alcoholism, Steve Dalkowski still had it in him to be a top performer and one of the most popular players in the league.

In Mexico during the last season of his career, Dalko was not a washed-up pitcher at the end of the line. He was one of the most solid, and at times brilliant, players on the team.