Note from author: I first wrote this article around 2015-16. I wrote it after about a decade of teaching apologetics and philosophy at theologically conservative seminaries. That experience had left a bad taste in my mouth (though it wasn’t all bad). A dogmatic fundamentalism infected the theological world I inhabited, and to stay in the good graces of that world seemed to require mouthing the right formulas even though no one deep down seemed to believe them. This was especially true about the doctrine of hell. It is now the latter half of 2023, and it seemed time for me to revise this article, getting some of my own ego and bad feelings out of the way to provide a more dispassionate treatment of this fraught topic. But don’t expect perfection—the topic still evokes strong feelings from me and from most people.

1 Consigning People to Heaven and Hell

Actress Jessica Alba, in a 2015 Vanity Fair article, describes the loss of her faith at age seventeen when she “fell crazy in love with a cross-dressing ballet dancer who had a baby and was bisexual. I was like, ‘There’s just no way he’s going to hell!’” Alba, it seems, reasoned that Christianity consigns a lot of good people to hell, so Christianity must be false.

To Alba’s rejection of Christianity, the usual Christian response is, “No one is really good. We’ve all sinned. It’s only by God’s grace that we can be saved. Given our present sinful state, hell is our natural destination. It doesn’t matter whether the cross-dressing ballet dancer is a really sweet guy. Without faith in Christ, he and all others are on their way to hell.”

Was Alba familiar with this explanation of hell? Growing up as a “devout born-again Christian,” she no doubt was. Did she previously accept this explanation? Probably so, since her cross-dressing friend, it seems, confronted her with an impossible choice: either reject Christianity or think that her friend was on his way to hell.

But what does it even mean to say “someone is going to hell”? For years I’ve watched Christians and non-Christians discuss the topic of hell, and the one lesson I’ve drawn is that we are tempted to think we know more about people’s ultimate destinies than we actually do, and that includes confidently consigning people to hell or to heaven.

It bears underscoring that God alone knows eternal destinies. It’s therefore not for us to say who’s in and who’s out regarding hell, or for that matter to offer odds about the likelihood of individuals ending up in hell (e.g., “He has a 99 percent chance of landing in hell”) or for that matter to put too much confidence in logical reasonings or theoretical grounds for membership in hell (e.g., “He has not accepted Christ, so if he were to die at this moment, he would be in hell”).

Rob Bell begins his book Love Wins by describing a church exhibit on peace that included a quote from Gandhi. To the quote someone attached a sticky note: “Reality Check — He’s in hell.” Bell used this incident to illustrate the what he regards as the harshness and presumption of Christians who think they know who’s going to hell. He’s no doubt right that many do not treat this topic with the humility it warrants. But then he uses this incident as a springboard to argue that God’s love eliminates the very possibility of hell.

Most Christians, like the sticky note writer, are not so ready to give up on hell. And that holds doubly for heaven. In fact, many Christians are even quicker to consign people to heaven than to hell. Bell does so as a matter of course (everyone for him ends up in heaven because, for him that’s what it means for love to win). But how many times have I heard a preacher talk about someone who has died and is now in the arms of Jesus, reunited with loved ones, residing in heaven?

To comfort grieving family and friends, that seems the appropriate thing to say. Moreover, we’ve seen the consistently well-lived life of certain people and the winsome witness to their faith, and we conclude, reasonably it seems, that if there’s a heaven, they will surely be there.

Of course, people with a record of good works and faith may be living a lie. What if Jerry Sandusky, the pedophile coach at Penn State, had died a decade before his criminal trial? Wouldn’t many people, especially for his “charitable work with boys,” have concluded that he was a wonderful man who was on his way to heaven? Or more recently, take the revelations about Ravi Zacharias, who was found after his death to have been a sexual predator.

But in general, consigning people to heaven raises few eyebrows. As it is, the Bible gives more cause to say someone is in heaven than in hell. On the cross, Jesus says to the thief next to him “today you’ll be with me in paradise.” That certainly seems to be clear proof that the thief is going to heaven. Jesus seems to guarantee it, and he, as the savior of the world, he is in a position to guarantee it.

But what about the other thief, who did not embrace Jesus on the cross — the one who reviled him? Jesus did not say to him, so far as we know, “today you’ll be with the Devil in hell.” There thus seems to be an asymmetry here: Jesus is willing to tell particular individuals that they are on their way to heaven, but not that they’re on their way to hell (though Jesus does speak in general terms about people going to heaven or hell throughout the Gospels, such as in the parable of the sheep and goats in Matthew 25).

Indeed, there’s only one human being mentioned in Scripture where the evidence seems convincing that this person is in hell (and thus that hell is not an empty set). That would be Judas. Jesus comments on the person who would betray him, namely Judas, as follows (though note that he does not address Judas by name): “it would have been better if he had never been born.” Now, it seems that if heaven is real and as happy a place as it’s supposed to be, then anyone who ends up there is better off being born. So it seems reasonable to conclude that Judas is not in heaven. And since heaven and hell are mutually exclusive and exhaustive (as seems a reasonable assumption), the conclusion follows that Judas is in hell. Case closed.

Or is the case really closed? The argument just given seems certainly cogent. And there are other instances in the New Testament where eternal destinies of individuals seem plainly in doubt (take Ananias and Sapphira in Acts 5, who both fall dead for, as Peter puts it, “lying to the Holy Spirit”). Still, I would suggest the logic here is not fully convincing, and that’s because all reasoning about who goes to hell and who doesn’t may be inherently problematic. The problem is that Scripture and Christian theology generally give so many mixed and paradoxical messages about hell.

2 How Bad Is Hell?

Hell, in Scripture, is portrayed as a really bad place: no one consigned there wants to stay there. In Jesus’ story in Luke 16, often titled “The Rich Man and Lazarus,” the rich man deeply distressed about having ended up in hell. So much so, in fact, that he doesn’t wish hell on anyone else. He thus urges father Abraham to send word, via the poor man Lazarus, to his brothers so that they can be forewarned and thus avoid hell.

The rich man knows Lazarus because while they were both still alive, Lazarus had begged and suffered outside the rich man’s home. Unlike the rich man, Lazarus is spending eternity happily with Abraham. How the rich man and Abraham are able to communicate in the afterlife is left unspecified in the story. But alas, Abraham tells the rich man that sending Lazarus to his brothers is not an option. As Abraham explains, the rich man’s brothers should be listening to Moses. If they did, they wouldn’t be on their way to hell. That seems to be the upshot of the story.

But this story leaves a lot of theological question unanswered. Moses can’t save anyone. According to Christian theology, the law of Moses simply demonstrates our incapacity to follow God’s laws. No one gets into heaven by listening to Moses; one gets to heaven by listening to Jesus, who has superseded Moses.

But why then is Lazarus in Abraham’s bosom (heaven?) and the rich man in hell? Lazarus presumably predated Christ and so didn’t trust him to be his savior. Certainly there’s no evidence that Lazarus consciously received Jesus as his personal savior. Nor is it clear that Lazarus was an avid follower of Moses. In fact, since Christian theology teaches that all (other than Jesus) have sinned, it’s safe to say that Lazarus would at some point have violated Moses’ law (perhaps he coveted the food on the rich man’s table).

How then did Lazarus make it to heaven? Is Lazarus in heaven because he was poor and begging in front of the rich man’s house — does being poor and oppressed guarantee passage to heaven (calling to mind liberation theology’s preferential option for the poor and oppressed)? But in that case, let’s all be poor and oppressed, so that God will take pity on us and ultimately take us to heaven. At the same time, let’s also pity the rich, who are lulled by their riches, and will soon be consigned to hell.

Where is all this going? Among my very conservative Christian colleagues, the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus is a factual story — it really happened. But even among my conservative (but not very conservative) Christian colleagues, it is regarded as a story that could nonetheless have happened (the names, but not the story, have been changed to protect the innocent/guilty).

But perhaps the story is less about hell and more about being caught up in riches and losing one’s life to them. Or perhaps it is also meant to comfort the poor with the promise that the inequality they are now experiencing will soon come to an end (Karl Marx would regard such a promise as an “opiate,” but not all opiates are bad and some can be true). Perhaps it is about a lot of other things, like shaking the Pharisees out of their blindness and hypocrisy.

How painful is hell? The rich man was clearly in discomfort, but apparently not in such great torment that he was unable to communicate — he wasn’t screaming so uncontrollably that he couldn’t converse with Abraham. But perhaps the rich man really wasn’t in final hell (i.e., Gehenna, the ultimate destination of the damned, the place of burning and eternal torment), but only in temporary hell (i.e., Hades, the temporary holding area for the damned until they receive their eternal judgment from God on the way to Gehenna).

Is the pain of final hell, which in the sequel we’ll simply call hell, worse than the worst pain people experience on earth? To listen to Jonathan Edwards’s sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” it seems reasonable to conclude that no earthly pain can compare to the pain of hell:

Is the pain of final hell, which in the sequel we’ll simply call hell, worse than the worst pain people experience on earth? To listen to Jonathan Edwards’s sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” it seems reasonable to conclude that no earthly pain can compare to the pain of hell:

The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider, or some loathsome insect, over the fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked; his wrath towards you burns like fire; he looks upon you as worthy of nothing else, but to be cast into the fire; he is of purer eyes than to bear to have you in his sight; you are ten thousand times so abominable in his eyes as the most hateful venomous serpent is in ours. You have offended him infinitely more than ever a stubborn rebel did his prince.

If the supreme being of the universe is this angry and upset with you, then you are in serious trouble. In that case, shouldn’t you expect more torment in hell at the hands of God than any torment earth has to offer. Christians have been known to comfort themselves with the maxim “earth has no sorrow that heaven cannot heal.” But for the damned, it would seem “earth has no sorrow that hell won’t amplify.”

Hell as the ultimate place of torment is implicit in Jonathan Edwards., Thomas Aquinas makes this view of hell explicit (all quotes from the Summa Theologiae):

The unhappiness of the damned surpasses all unhappiness of this world. [PIII/suppl-Q98-A3]

In the lost there will be a succession of punishments, so that the notion of something future remains there, which is the object of fear. [PII/1st-Q67-A4]

The disposition of hell will be such as to be adapted to the utmost unhappiness of the damned. [PIII/suppl-Q97-A4]

Quotes like this from Edwards and Aquinas seem at odds with the love and mercy of God toward humanity. Moreover, such remarks can be used to justify the worst atrocities in the name of religion since any torment or torture, if it keeps even one sinner from hell, will then more than make up for the pain inflicted in this ephemeral life.

Jonathan Edwards has been held up as the greatest of American theologians and Thomas Aquinas as the greatest of Catholic theologians. Yet does anyone actually such statements? As theology professors required to sign statements of faith at conservative theological institutions and denominations, my colleagues and I would exhibit due deference to Edwards, Aquinas, and others even as they wrote such things.

Yet does anyone take such pronouncements seriously and without qualification? I’ll attempt to show shortly that no one does. Just to be clear, there’s more to the theology of Edwards and Thomas than these statements about hell. But in their pronouncements about hell and divine vengeance, it’s hard to say that they were “taken out of context.” They say what they say. Their words are stark, harsh, grim.

But back to the question at hand: how painful is hell? If the mildest experience of hell is worse than the worst experience of pain on earth, that would be truly horrific (by contrast, Dante’s outer circles of hell were a cakewalk). But let’s spend a moment and think through what it would mean for hell at its best to be worse than earth at its worst.

In that case, God would have to attune our being (our resurrected bodies?) to be exquisitely capable of pain. But more than that, God would need to design those consigned to hell for the express and only purpose of experiencing pain, ever increasing pain, pain that at its start dwarfs all the pain of the world, and that, if Thomas is to be believed, will only intensify throughout eternity. Thomas again:

The fire which will torment the bodies of the damned after the resurrection is corporeal, since one cannot fittingly apply a punishment to a body unless that punishment itself be bodily. [PIII/suppl-Q97-A5]

In order that the happiness of the saints may be more delightful to them and that they may render more copious thanks to God for it, they are allowed to see perfectly the sufferings of the damned. [PIII/suppl-Q94-A1]

Comment: Christian physician Paul Brand coauthored with Philip Yancey some interesting books on pain. Brand was one of the key movers in the cure of leprosy/Hansen’s disease. This disease attacks nerve cells, thereby removing pain and thus causing people with the disease to injure and disfigure themselves because they lack the natural protection made possible by pain. Brand’s point in these books was that pain is a gift, which serves a benefit. Hence the title of one of his books: The Gift of Pain: Why We Hurt and What We Can Do about It. As this book makes clear, the incapacity to experience pain is more terrifying than pain itself. Pain is a response and defense to an attacked good. There is thus something perverse when theologians characterize hell as a place that makes pain an end in itself. What if hell is the total absence of pain, a total numbness to evil and acceptance of it without any resistance? I’m not saying I accept this view, but it is not entirely far fetched.

In case the idea of hell’s pain at its mildest exceeding earth’s pain at its most extreme isn’t quite grim enough, let’s not forget that Christian theology traditionally teaches gradations in rewards and punishments, so one wonders what hell at its worst would be.

Clarification: In the five quotes by Thomas Aquinas given above, I am actually representing his views on hell and not just views to which he gives expression. His Summa Theologiae is constructed as a set of articles each of which begins by stating a disputed point, then offering some objections that Thomas doesn’t actually accept, then stating his actual position, and finally offering his own responses to the previously raised objections. In all five quotes above, I’m going with what Thomas actually believes. This can be contrasted with the following quote about hell widely attributed to Thomas, but which appears in the objections of such an article and thus doesn’t actually reflect his views: “The magnitude of the punishment matches the magnitude of the sin… Now a sin that is against God is infinite. The higher the person against whom it is committed, the graver the sin — it is more criminal to strike a head of state than a private citizen — and God is of infinite greatness. Therefore an infinite punishment is deserved for a sin committed against God.” [PII/1-Q87-A4] Thomas actually doesn’t hold to the latter view.

3 Our (Pretended) Belief in Hell

It’s natural for people who haven’t been convinced of such a gruesome and unrelenting view of hell to reject it as untrue (like Jessica Alba in the introduction to this article) or at least to question its truth. Certainly one can cite biblical proof texts that agree with the teachings on hell such as by Jonathan Edwards or Thomas Aquinas. Consider, for instance, “They [i.e., the damned] will be tormented with burning sulfur [this is where we get “fire and brimstone”] in the presence of the holy angels and of the Lamb. And the smoke of their torment will rise for ever and ever. There will be no rest day or night.” (Rev. 14:10–11)

Leaving aside debates about the proper interpretation of such biblical passages and what truths they may rightly be said to teach about hell (debates that show no sign of getting resolved any time soon), let’s ask a related but different question, and one that does admit resolution: Does anyone really believe such teachings, namely, that hell at its mildest is more painful than earth at its worst? Sure, people may pretend to believe that the answer to this question is Yes. But pretending to believe is different from actually believing. Actual belief means acting on the belief, and with hell no one acts as though it’s really that bad.

How can I say that we merely pretend to believe in hell’s exceeding horribleness? Consider these words of 1 John 3:17: “How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses help?” If hell is really as bad as Edwards and Thomas make out, then the avoidance of hell is people’s most urgent need, bar none. Starvation, disease, war, natural disaster, and torture all would in that case pale compared to what awaits people in hell.

But why, then, are Christians doing so little to keep people from going to hell? Why do we give so little to missions or charities? Why don’t we make soul winning our number one priority? Why do we waste so much time watching and playing sports? Why do we put such a premium on leisure activities, such as hunting and fishing, or quilting and scrapbooking? Why do we spend so much money on vanities such as cosmetic surgery, designer clothes, and expensive jewelry? Why do we fast and pray so little? Why do we spend so much time and energy on theological squabbling (2 Timothy 2:23-24)?

If hell is as bad as Edwards and Thomas make out, then there is no respite, no break, no relief for the inhabitants of hell. Prayers won’t help them. Care packages won’t get delivered. Well wishes will be in vain. Accordingly, there is nothing — absolutely nothing — to be done to lighten the load of someone in hell. So any good we can do for people, we must do NOW. And the ultimate good then becomes keeping people from going to hell. After all, heaven seems well capable of taking care of itself. Once you’ve passed heaven’s gate, don’t you have it made?

Peter Singer, an atheist and villain for many Christians, spends 25 percent of his income to help the poor. By contrast, U.S. Christians give about 4 percent of their incomes to charities. According to Singer, if we see someone in dire need, we are morally obliged, even at grave cost to ourselves, to try to meet that need. Christians may demur about the ethical principles by which Singer arrives at this conclusion, but the conclusion that desperate human need demands action to meet that need seems entirely consonant with Christian belief. Consider, for instance, James 2:14–18:

What good is it, my brothers and sisters, if someone claims to have faith but has no deeds? Can such faith save them? Suppose a brother or a sister is without clothes and daily food. If one of you says to them, “Go in peace; keep warm and well fed,” but does nothing about their physical needs, what good is it? In the same way, faith by itself, if it is not accompanied by action, is dead. But someone will say, “You have faith; I have deeds.” Show me your faith without deeds, and I will show you my faith by my deeds.

If hell is as urgent and dire a peril as claimed by Edwards and Thomas, then it seems that the majority of Christians act as though Singer and James may safely be ignored. Indeed, do any Christians demonstrate such a belief in hell by their actions? But how else do we know what people actually believe except by their actions? Indeed, it’s easy to say we believe anything at all. Pretense is always easier than action. And only action demonstrates belief.

Now one might argue that the failure of Christians to act with the urgency that hell demands does nothing to undercut the reality of hell and its unfathomable pain for the damned. There’s simply the truth of hell and then simply our failure as Christians to adequately live out that truth. We’re all imperfect, after all.

But consider again 1 John 3:17: “How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses help?” And what greater need is there but to escape hell? So, if we’re not doing everything in our power to prevent people from going to hell, and if hell is the worst thing that can befall anyone, then this verse seems to teach that God’s love is not in us.

But if God’s love is not in us, then we’re not truly Christians. And if we’re not truly Christians, then we’re not on our way to heaven. But since heaven and hell are our only two possible destinations, we’re on our way to hell. The logic here suggests that since none of us seems fully committed to helping (and thereby loving) those in danger of hell, in fact all of us are on our way to hell.

Now I’ll grant that the logic leaves something to be desired. But it’s no worse than the logic used to justify that complacent Christians can be on their way to heaven while the bulk of humanity is on its way to hell. The logic here runs something like this: “Christians are saved by faith, not by works. Thus, when they don’t do everything in their power to prevent people from going to hell, that’s too bad, but it doesn’t jeopardize their own salvation and thus their ultimate success in getting to heaven.” In this way, logic can help complacent Christians to justify their complacency.

The real question, however, remains, namely, does faith trump the absence of God’s love in our hearts, as demonstrated by our failure to meet people’s most urgent need to avoid hell, so that faith gets us to heaven despite our lack of love? It would then seem that we really don’t need to have God’s love in our hearts for our needy neighbors. All we need is faith (though evidently not the faith of James 2, the faith that without works is dead).

But if faith without love can get us into heaven, what do we do with 1 Corinthians 13, in which the Apostle Paul says that faith, hope, and love are great, but that the greatest of these is love? If such reasonings about hell have an air of unreality, perhaps it’s as I indicated earlier: reasonings about hell resist firm conclusions.

Comment: Given that Christians don’t seem to do nearly enough to keep people from going to hell if they really think hell is so bad, the question arises what they should be doing to keep people from going to hell. I hinted that among the things they might be doing is Christian missions and alleviation of poverty.

But these are non-coercive. If hell is really so very bad and if Christians have the energy and will to prevent people from going there, coercion becomes readily justifiable, especially if those on their way to hell are seen as being so recalcitrant and misguided that they are leading others to hell. The Spanish Inquisition and the Taliban provide ready examples of this mentality.

Imagine someone to whom the Gospel is preached and who receives Christian charity, but still does not explicitly acknowledge faith in Jesus. Why not torture such a person into accepting Jesus, perhaps even killing that person right after giving evidence of faith lest the person recant once the torture is removed? Alternatively, if they still resist under torture, why not give them a slow and painful public death to deter others from following their example?

As it is, torture in so-called Christian nations has a long history. In fact, it seemed to get worse in the aftermath of the Reformation, and the skepticism of the Enlightenment was to a significant degree a reaction against that inhumanity and violence (see the relevant volumes of Will Durant’s The Story of Civilization).

If God is the master torturer, and if he designed hell for maximal pain, then humans would merely be imitating their master, giving people a foretaste of the hell to come. A Google search on images of medieval torture implements confirms this point. Torture could even be rationalized as an act of love, helping people avoid the torment of eternity by exposing them to the relatively mild and temporary torments of earth.

This entire line of reasoning is absurd and obscene. I recount it because it has been deeply influential.

4 Conscious Explicit Faith in Jesus

I’ve suggested that logical reasoning about hell is problematic, but perhaps we’re giving up on logical reasoning too soon. Let’s therefore ask if there are any clear criteria for who is in hell and who is not. In other words, is there some clear way of deciding whether someone is going to hell? When I used to teach at conservative theological seminaries, the safest course for maintaining one’s position was to take the hardest line possible on hell: only those with a conscious explicit faith in Jesus are exempted from hell; the rest face unending conscious torment.

Amazingly, this line was often taken without any qualification whatsoever. Take any less extreme view of hell, and you were in danger of being regarded as heretical and thus of losing your job. I even saw it stated by one professor at a seminary where I taught that only this view (i.e., conscious explicit faith in Christ alone avoids conscious unending torment) helps us “to properly love the lost and work most effectively for their salvation.” This is almost verbatim.

But who really believes this? To be sure, we can mouth any words we like and pretend to believe them. But does anyone truly believe that only conscious explicit faith in Jesus is a necessary condition for avoiding hell and that without such faith one faces unending conscious torment? It seems that all but the most dogmatic, when pressed, will admit to there being certain exceptions.

4.1 Exception: Infants

As a first exception, consider infants who die before they have language and can learn and believe the Gospel, thereby precluding that they can have conscious explicit faith in Jesus as their savior? Most people would regard this as a convincing exception. But not all.

Augustine, for instance, held that infants who die unbaptized go straight to hell. And yet, baptized infants for Augustine did go to heaven. The church, as the agent of baptism, could thereby guarantee its necessity in the economy of salvation. Yet even for Augustine, conscious explicit faith in Jesus was not necessary to avoid the unending conscious torment of hell, provided a person was baptized and too young to know the Gospel.

Since Augustine’s day, and especially in our own, Catholic theology has gotten softer on the topic of hell. When I was learning the catechism for my first holy communion in the Catholic church 55 years ago, my teacher assured me that infants that died unbaptized didn’t in fact go to hell. Instead, they went to Limbo, a place of natural happiness, but lacking the supernatural happiness of heaven where the baptized believers enjoy the beatific vision and union with God.

Limbo lacks the pain of hell but also the full glory of heaven. I remember as a eight-year old being troubled by the catechism teacher’s cavalier dismissal of the fate of these unbaptized infants and the evident unfairness, to my mind, of it all.

Since my experience 55 years ago, Catholic theology has grown softer still. It now appears that Limbo is itself in limbo — that the Catholic Church is seriously considering retiring Limbo and opening up heaven to all infants who die, baptized or unbaptized.

The Vatican’s Latest on Limbo: “It is clear that the traditional teaching on this topic has concentrated on the theory of limbo, understood as a state which includes the souls of infants who die subject to original sin and without baptism, and who, therefore, neither merit the beatific vision, nor yet are subjected to any punishment, because they are not guilty of any personal sin. This theory, elaborated by theologians beginning in the Middle Ages, never entered into the dogmatic definitions of the Magisterium, even if that same Magisterium did at times mention the theory in its ordinary teaching up until the Second Vatican Council. It remains therefore a possible theological hypothesis. However, in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992), the theory of limbo is not mentioned. Rather, the Catechism teaches that infants who die without baptism are entrusted by the Church to the mercy of God, as is shown in the specific funeral rite for such children. The principle that God desires the salvation of all people gives rise to the hope that there is a path to salvation for infants who die without baptism (cf. CCC, 1261), and therefore also to the theological desire to find a coherent and logical connection between the diverse affirmations of the Catholic faith: the universal salvific will of God; the unicity of the mediation of Christ; the necessity of baptism for salvation; the universal action of grace in relation to the sacraments; the link between original sin and the deprivation of the beatific vision; the creation of man ‘in Christ’.”

SOURCE: www.vatican.va/…

It seems, then, that even those who claim that conscious explicit faith in Jesus is required to avoid conscious eternal torment will admit this one exception. But once there’s an exception, there’s a slippery slope, inviting more exceptions. What do you do, for instance, with my autistic son, who’s in his early twenties, but is nonverbal and incapable of understanding the Gospel in any “conscious explicit” sense (he functions at about the level of a 2- or 3-year old)? Presumably, here we have another exception.

Comment on Conservativeness: When it comes to being conservative, it’s worth bearing in mind that there’s always someone more conservative than you, even if you think you’re as conservative as it gets (a similar observation holds for liberalism, but that’s not relevant to this discussion on hell since most theological liberals reject hell outright).

Thus even hyper-conservatives will find their conservativism questioned by ultra-hyper-conservatives, who regard them as soft on tradition and orthodoxy. In looking up the status of Limbo in Catholic theology, for instance, I came across a website with the domain name www.traditioninaction.org, insisting that Catholic teaching about Limbo remain unchanged.

TraditionInAction.org has an article titled “24 Reasons Why Not To Reject Limbo.” Included among these reasons are the following:

- Because Pope Pius VI, in a formal magisterial decree, denounced the rejection of Limbo as “false, rash, slanderous to Catholic schools.”

- Because it is an unchangeable article of Faith, taught infallibly by the Second Council of Lyons and the Council of Florence that the souls of those who depart this life in the state of original sin are excluded from the Beatific Vision.

- Because Pope Sixtus V taught in a 1588 Constitution that victims of abortion, being deprived of Baptism, are “excluded from Beatific Vision,” which is one of the reasons Sixtus V denounced abortion as a heinous crime.

- Because the theory that babies who die before Baptism attain Heaven was never taken seriously by the Fathers, Saints, Doctors and Popes of the Church throughout History.

- Because there are countless Catholic parents throughout the ages who have suffered the misfortune of miscarriages, but were not the least bit tempted to discard the teaching of Limbo, since they knew the souls of these unbaptized babies enjoy a state of natural happiness for eternity.

So when I say that contemporary Catholic theologians have gotten soft about consigning infants who die in their infancy to hell or Limbo, there will be exceptions even in this day and age. For some people there’s no such thing as being too conservative!

4.2 Exception: The Unaccountable

Usually, theologians who want to take a hard line on hell but who don’t want to seem unreasonable by consigning infants to hell introduce a convenient theological construct known as “the age of accountability.” To justify this construct, Isaiah 7:16 is often cited, which speaks to the time in a child’s life before he/she knows to choose good and refuse evil. Presumably, before that time, the child is safe from hell — how can a child (or adult for that matter) who doesn’t know the difference between good and evil be held accountable for moral fault and thus be consigned to the punishment of hell?

Augustine, with his view of original sin or guilt, was fine with consigning to hell even those who had not reached the age of accountability. But most theologians these days regard it as permissible to believe that God lets all into heaven who have not reached the age of accountability.

But the age of accountability is a strange thing when examined closely. When exactly does it begin? Does it happen gradually? If so, when is there enough accountability so that without conscious explicit faith in Jesus, one goes to hell? Or does it happen all at once, in a threshold effect, so that one day one wakes up, finds oneself to have reached the age of accountability, and thus, if not a Christian, is in danger of hell?

Imagine Alice and Bob. Alice and Bob live in a region of the world where no one is a Christian (i.e., no one there has conscious explicit faith in Jesus). Alice, had she lived another day, would have reached the age of accountability. But she happens to die just before she would have reached the age of accountability, and so goes to heaven. Bob, on the other hand, is less fortunate. He wakes up one morning to find that he’s reached the age of accountability, but that very day he dies. Sadly, he goes to hell.

An example like this raises doubts about whether the age of accountability should play any role in our deliberations about who goes an doesn’t go to hell. Still, the age of accountability seems to have some relevance to such deliberations. Certainly, newborns are unaccountable and thus not properly punished for any sins, which they presumably could not, because of their immaturity, have committed or be predisposed to commit. Here should be added severely mentally disabled individuals.

At the same time, even young children quickly engage in selfish and even cruel actions, such as stealing from, bullying, and ostracizing their peers. Moreover, guilt is readily apparent on their faces. Is age of accountability a legitimate theological construct with a true point of reference in reality or is it more a convenient fiction? And should it play any role in our deliberations on hell? At the very least, it complicates our understanding of hell.

4.3 Exception: Those Who Predated Jesus

As another exception to the claim that only conscious explicit faith in Jesus can prevent conscious eternal torment in hell, consider all those who lived before Jesus’ cross and resurrection. Obviously, they couldn’t have had conscious explicit faith in Jesus because, before God took human form in the historical person of Jesus, there was no Jesus to serve as the object of conscious explicit faith. So what happened to all those people?

The traditional theological response is that there were true worshippers of the one true God before Jesus, who worshipped God with what light they had — and that this was therefore good enough to get them into heaven. That seems reasonable. All the same, when the fullness of God’s light came to earth in Christ Jesus, then people were obliged to believe explicitly in him. Before that, God made allowances.

There’s also a tradition, adverted to in the Apostle’s Creed, of Jesus having descended into hell (Hades) and preaching to its inhabitants. This is consistent with 1 Peter 3:18–19: “Christ was put to death in the body but made alive in the Spirit. After being made alive, he went and made proclamation to the imprisoned spirits.”

This passage raises many questions, not least why Jesus needed to preach to the dead in Hades, what was the efficacy of this preaching, and whether any of those imprisoned spirits found liberation as a consequence of that preaching, thus ending up in heaven rather than hell (in this case, Gehenna — the final hell).

It’s the traditional Christian view that we have only this life to make our peace with God and that after the moment of death, we’ve exceeded the statute of limitations on God’s mercy. A common proof text in this regard is Hebrews 9:27: “It is the destiny of people to die once and after that to face judgment.”

Putting all these disparate pieces together, however, seems less than straightforward. It’s evident from the Old Testament that people could be saved apart from the covenant of Abraham. Take Melchizedek, for instance, mentioned in Genesis 14, who is called a priest of the most high God and who, in Hebrews 5–7, is taken as emblematic of the priesthood of Jesus. Or consider Job, who, despite his travails and not being an Israelite, was obviously in right relationship with God and on his way to heaven.

It seems, then, that you can get to heaven before New Testament times if you’re righteous and worshipping the one true God (righteous here evidently doesn’t mean sinless, since the only sinless human being is Jesus; add to this list of sinless people Mary, Jesus’ mother, if you accept Catholic theology, though in Mary’s case, she was kept from sin rather than being entirely free of a sin nature). But after Jesus’ cross and resurrection, it becomes mandatory to have conscious explicit faith in Jesus to avoid hell.

But that can’t be right. Let’s bring back Alice and Bob, only this time Alice and Bob are righteous worshippers of the one true God who are contemporaries of Jesus but live so far from the land of Israel that they never heard of him. Alice has the good fortune of dying before Jesus’ cross and resurrection, and so goes to heaven. Bob, sadly, dies right after Jesus’ death on the cross and resurrection. Given that Jesus’ cross and resurrection are now a fait accompli, and given that God henceforward demands conscious explicit faith in Jesus for salvation, Bob goes to hell. This seems absurd.

But if Bob’s death immediately after Jesus’ cross and resurrection is not enough to consign him to hell provided he is a righteous worshipper of the true God, albeit without conscious explicit faith in Jesus, then why should it matter if Bob dies a week, a month, a year, a decade, a century, or a millennium after Jesus’ cross and resurrection? Why should time, or for that matter distance, from Jesus’ cross and resurrection matter?

4.4 Exception: The God-Fearers

Scripture itself suggests that spatiotemporal limitations that keep people from conscious explicit faith in Jesus cannot keep them from heaven or consign them to hell. Consider Paul in Romans 2:14–16: “When the gentiles, which have not the law, do by nature the things contained in the law, these, having not the law, are a law unto themselves, which show the work of the law written in their hearts, their conscience also bearing witness, and their thoughts the mean while accusing or else excusing one another, in the day when God shall judge the secrets in people’s hearts by Jesus Christ according to my gospel.”

This is a remarkable passage, and it’s evident that Paul holds that there really are righteous gentiles such as he describes since in context he’s contrasting such gentiles with Jews who have the law but are not living it. Yet we need look no further than the book of Acts for an example of such a righteous gentile, namely Cornelius, about whom and his family Peter has this to say (Acts 10:34–35): “I now realize how true it is that God does not show favoritism but accepts from every nation the one who fears him and does what is right.”

Granted, Peter did also share the Gospel with Cornelius, who then became a conscious and explicit believer in Jesus. But surely there were others like Cornelius, God-fearers as they were known, who were likewise accepted with God, but without conscious and explicit faith in Jesus. This raises the obvious question: If someone is accepted with God, can that person be going to hell? The answer seems equally obvious: No.

4.5 Exception: Retrograde and Anterograde Amnesiacs

As still another class of exceptions to the rule that conscious explicit faith in Jesus is required to escape conscious eternal torment in hell, consider two types of amnesiacs, the retrograde and the anterograde. There are people with retrograde amnesia who cannot remember who they were and what they’ve done before an injury or illness. Life, in a sense, begins for them anew. We can assume they are old enough and have sufficient cognitive and moral faculties to have reached the age of accountability. Moreover, before their amnesia, let’s assume they were sinners and on their way to hell. But now they have no recollection of their past sins.

Is the slate now clear for them? Do they get to start life afresh? What if they die right after suffering their amnesia but before committing any new sins? Do they now go to heaven? What if they had accepted Jesus in their old life, but now can’t remember doing so and henceforth remain unresponsive to the Gospel? God no doubt knows how to sort this out, but demanding conscious explicit faith of retrograde amnesiacs requires some qualification.

In such ruminations about hell, even more disconcerting is anterograde amnesia, which usually is associated with certain brain lesions resulting from an accident. The victim, in this case, is able to recall his or her life perfectly up to the point of the accident, but thereafter only form memories of about a fifteen-minute duration. In other words, the person has short-term memory, but is unable to form new long-term memories. Let’s imagine therefore someone who suffered such an accident, reached the age of accountability, and was sufficiently sinful as to be on his/her way to hell before suffering amnesia.

The problem now, however, is that this person, without being able to remember anything long-term, is essentially living in the past. In the past, that person had no conscious explicit faith in Jesus. In the present, unfortunately, any conscious explicit faith in Jesus will be lost in fifteen minutes. Thus, day after day, the Gospel may keep getting shared with this person. Some days the person accepts the Gospel in one fifteen-minute time block, only promptly to forget having accepted it, and thereafter for the rest of the day refuses to accept it.

Comment: Once such amnesiacs experience an event, the clock is literally ticking, and they will not remember the event within a few minutes. Thus, if there’s a funny story from their past (before the amnesia), they’ll recount it endlessly because they won’t remember that they just told it. If they’ve eaten a meal and a few minutes are up, they won’t remember that they’ve eaten.

Is a person with anterograde amnesia going to heaven or hell? What if this person died right before the end of a fifteen-minute time block during which he or she accepted Jesus, thus still having conscious explicit faith in Jesus? Would that ensure heaven? What if the person died only a moment later, having entirely forgotten the Gospel and his or her acceptance of it? No neat and pat formula seems capable of deciding the eternal destinies of such amnesiacs.

5 The Celebration of Life, Or Not

Leaving aside God-fearers and amnesiacs, let’s return to the very young and/or unaccountable (i.e., those who have yet to reach or are incapable of reaching the age of accountability). Once these are automatically admitted to heaven (or at least excluded from hell by going to Limbo), another strange thing happens, which was hinted at in the first of our Alice and Bob examples.

Normally, we regard it as tragic when a young child dies — so much unfulfilled potential, so many unmet dreams, so many songs that will never be sung. On the other hand, when someone dies in old age after a full, rich life, we don’t regard it as tragic. Instead, even if there are tears and loss, we also celebrate the life. And sometimes we even celebrate the life when the person isn’t that old but has left a positive mark on the world. Consider, for instance, the following memorial service for the Hawaiian singer IZ:

But if those under the age of accountability automatically go to heaven, then really we should be celebrating their deaths. After all, they’re now enjoying the delights of heaven. Conversely, if those over the age of accountability don’t automatically go to heaven, then we should approach their deaths with misgivings. Thus, when older people die who have not made explicit profession of faith in Jesus, we should lament their deaths as a tragedy in which hell has (or may have) just acquired new inhabitants. Our differing reactions to death depending on age of the dying person thus seem in tension with traditional teachings about hell.

Consider again my autistic son. Whatever one means by the age of accountability, he hasn’t reached it. And yet I yearn for him to be able to communicate with a full, age-appropriate set of language abilities. I recall one of his special education teachers telling me that he was communicating and conversing with her through an iPad, but when I examined what that communication entailed, it was largely just random touches by him of various icons. I have never held a real conversation with my son. And I sorely miss not being able to do so.

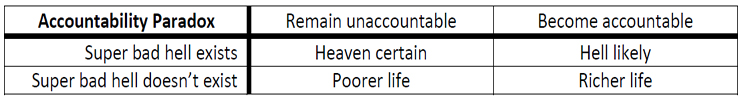

But if my autistic son did come out of his autism and start to communicate verbally, with sufficient comprehension so that he could have conscious explicit faith in Jesus, he would also have the option of rejecting the Gospel. Hell would thus become a danger to him in a way that it is not now. So, which should I prefer, my son to stay autistic and be guaranteed a place in heaven, or for him to come out of his autism and risk hell, perhaps even the sort of hell that Edwards and Thomas are convinced would await him if he rejected Christ?

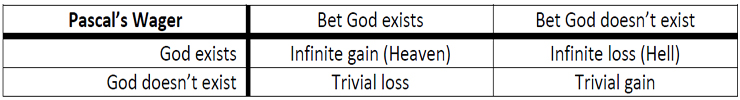

In Pascal’s famous wager, you’re better off betting on God and heaven being real because if they are, then you’ll be more likely to get there; but if you think that they are unreal, then if they are in fact real, you’ll end up in hell. The risk of being wrong about hell thus totally outweighs the risk of being wrong about heaven. So a risk analysis suggests you should believe or pretend to believe that heaven is real.

But in that case, a parallel risk analysis should get us to prefer that the young die and not go on to maturity so that they don’t risk the very possibility of hell. Accordingly, we should wish for and applaud the dying of the very young. Similarly, we should prefer that the unaccountable stay unaccountable.

As another variation on this theme, consider the view of many pro-life people in the abortion debate that human life starts at conception, the moment the father’s sperm locks into the mother’s egg. Now, it seems that most of these conceptions never implant in the womb, and thus end in death. And then there are all the fetuses that are deliberately aborted and end in death.

If all these are full human lives, then they must have an eternal destiny in heaven or hell. And since we are ruling out hell for newborns, infants, and those who haven’t reached the age of accountability, we are compelled to regard all these human lives as likewise ending up in heaven (if they end up anywhere in eternity — let’s lay Limbo aside in the sequel).

But consider what that means. If we think that conscious explicit faith is necessary for those capable of it to avoid hell, then we should be overjoyed at all these (naturally) aborted embryos and (artificially) aborted fetuses. All of them are then on their way to heaven. In fact, abortion could then be seen as an industry for populating heaven. Abortion, if you will, turns maternity wards into eternity wards (a turn of phrase due to the cartoonist Wayne Stayskal).

But such conclusions are monstrous. Isn’t it better in the grand scheme of things if humans come to maturity and live a full life — mistakes, vices, warts and all? Doesn’t that make for a more interesting, more purposeful, more meaningful universe? What sort of worldview regards it as a net benefit to keep humans in a state of immaturity in order to forestall hell?

Perverse incentives: If we knew for certain that fetuses and infants that die (with or without being baptized) all end up in heaven, it could provide an incentive to kill them — after all, we would thus ensure their eternal happiness since otherwise they risk the hell of Edwards and Thomas.

Reformed theology (i.e., the theology of John Calvin and his successors), it turns out, offers a way around such perverse incentives. Within that theology, only the elect go to heaven. Thus, in the Westminster Confession (a prime document of reformed theology), we read:

“Elect infants, dying in infancy, are regenerated, and saved by Christ, through the Spirit, who worketh when, and where, and how he pleaseth: so also are all other elect persons who are incapable of being outwardly called [i.e., the “unaccountable”] by the ministry of the Word.”

So, are all who die in infancy elect? The Westminster Confession sidesteps that question, neither affirming nor denying that infants and the unaccountable who die in that state are elect. The Westminster Confession thus blocks perverse incentives that would make abortion salvific. But in leaving open the possibility that some infants who die in infancy may be non-elect, it suggests a harshness and arbitrariness to divine election.

6. Money and Hell

The extreme view of hell has interesting implications for our use of money. By the extreme view of hell, I mean a view that, as much as possible, tries to maintain the formula “only conscious explicit faith in Jesus can prevent conscious eternal torment in hell,” allowing no more exceptions than absolutely necessary (such as infants and the unaccountable). Practically speaking, this view makes hell’s avoidance the ultimate good. To be sure, we can talk about heaven, with its beatific vision and divine union, as the ultimate good. But on the extreme view of hell, that’s merely the flip side of the same truth.

The extreme view of hell raises an interesting economic question. Specifically, on the extreme view of hell, how should we spend our money and resources? For me, this question is not academic. Early after my son John was diagnosed with autism, a severe form of it, my wife and I tried many alternative therapies. These were not cheap. I was earning extra money speaking on intelligent design at the time, and I recall a few years where we were spending tens of thousands of dollars annually to try to get him well (with only limited benefit to show for in the end). That was a lot of our disposable income.

Now, given the severity of my son’s autism and how, as we’ve already discussed, this guarantees his entry to heaven (even on the extreme view of hell), wouldn’t all that money have instead been better spent on Christian missions or in some other way to help people in danger of hell fire? With the funds spent trying to recover my son’s health, many people would likely have converted to Christ who now, because that money was never given, will never hear the Gospel and thus go to hell, if the extreme view of hell is true.

Accordingly, expressions like “charity begins at home” and “blood is thicker than water” would mean nothing, at least in my son’s case, if the extreme view of hell is correct. But who thinks this way? And if we don’t think this way, why do so many teach the extreme view of hell?

Digression: I personally take a hard line against abortion, infanticide, and euthanasia. But the extreme view of hell raises the prospect of “Christian euthanasia.” If the sick, the disabled, the weak, the criminal are sucking away resources that could be used to keep other people out of hell, might it not be better simply to kill off the former for the benefit of the latter, especially if the latter substantially outnumber the former?

Or course, there’s the problem that the executioner(s) in this case, by committing murder and thus violating the Sixth Commandment, would end up in hell. But any such executioner might derive some comfort, even in hell, knowing that he or she helped prevent many others from going to hell. Of course, overt advocates of “Christian euthanasia,” as I’m calling it, are likely to be few to zero.

But the logic of the extreme view of hell, in which only conscious explicit faith in Jesus avoids hell (minus a few minimal exceptions), should lead those holding this view to silently cheer whenever the death of certain resource-consuming people (the Nazis called them “useless eaters”) frees up funds that leads to a greater number of people avoiding hell and going to heaven. In this way, Christians would embrace a weird consequentialist ethics identical to the worst eugenicists of the past.

Just to be clear, I regard any such “Christian euthanasia” as a monstrous perversion.

7. What About Non-Christians?

Let’s shift gears and turn next to the eternal destiny of people who are not Christians. Take someone from a non-Christian faith. On the extreme view of hell, it would be wrong to say that this pers might go to heaven. But would it in fact be wrong?

Certainly, it would be wrong to say that non-Christians can’t go to heaven, period. After all, non-Christians can always become Christians by converting to Christianity (provided they’re not amnesiacs or too cognitively impaired). So the issue really is whether non-Christians as non-Christians and as remaining non-Christians can go to heaven. But how do we know whether anyone remains a non-Christian?

John Wesley, I’m told (though I’ve never been able to track down the reference), regarded it as possible for an unbeliever to become a believer (and thus go to heaven) between the moment of being knocked from a horse and breaking one’s neck, thereby dying instantly. Accordingly, in that moment, in that very fraction of a second from fall to death, God is able to save, turning a non-Christian into a Christian. Jesus says that with God all things are possible, so this would certainly be possible, and any Christian would presumably have to regard it as possible if taking Jesus at his word.

Nor does this scenario, in which someone is converted to Christianity and thus saved at the moment of death, presuppose that the person in question had been previously exposed to the Gospel. Thus, this scenario doesn’t require that the moment of death trigger a memory of the content of the Gospel, from prior conscious exposure to the Gospel, which then finds acceptance from the person and thus leads to his or her salvation.

Presumably, God could impart the essence of the Gospel to the person who is microseconds from death, elicit faith in those few microseconds, and thereby save the person. Increasingly in our day one reads of people unreached by the Gospel who have had visitations by Jesus and who thereupon become Christians. So what’s to prevent that from happening at the moment of death? In fact, we have no idea to what extent this may be happening. But it’s certainly a possibility on even the most conservative understanding of Christianity and hell.

So, in response to the question “Can a Muslim [or Mormon or Mithraite] be saved,” I would say “Sure.” As a Christian, I would add that ultimately it is only through Christ that one is saved, and thus that a Muslim, if saved, is saved in spite of rather than because of his/her religion. But the same could be said for any religion, even Christianity. It’s not religion that saves, not even Christianity, but the living Christ who rose from the dead and relates directly to our inner being. How this Christ chooses to commune with and thereby save us seems not for us to specify.

In reply, one might ask what’s the point of preaching the Gospel, which according to Scripture seems to be the preferred method by which people are saved (in 1 Corinthians 15, the Gospel is even referred to as “the power of God unto salvation”). Many people described as becoming Christian and being saved in the New Testament do so under the ministry of the Apostle Paul and do so in response to Paul’s preaching about Jesus. But there’s no contradiction here. God uses people preaching the Gospel to save people. But that does not preclude God imparting the saving power of the Gospel by other means.

Salvation worries. Consider the following passage from a young woman who was shot in the head for her faith and yet survived:

We human beings don’t realize how great God is. He has given us an extraordinary brain and a sensitive loving heart. He has blessed us with two lips to talk and express our feelings, two eyes which see a world of colors and beauty, two feet which walk on the road of life, two hands to work for us, a nose which smells the beauty of fragrance, and two ears to hear the words of love. As I found with my ear, no one knows how much power they have in their each and every organ until they lose one.

I thank [God] for the hardworking doctors, for my recovery and for sending us to this world where we may struggle for our survival. Some people choose good ways and some choose bad ways. One person’s bullet hit me. It swelled my brain, stole my hearing and cut the nerve of my left face in the space of a second. And after that one second there were millions of people praying for my life and talented doctors who gave me my body back. I was a good girl. In my heart I had only the desire to help people. It wasn’t about the awards or the money. I always prayed to God, “I want to help people and please help me to do that.”

These two paragraphs are from the Muslim teenager Malala Yousafzai (from her autobiography I Am Malala). She was awarded the Nobel Prize for her efforts to advance the education of Muslim women against the opposition of the Taliban.

Is Malala on her way to heaven because God, despite her lack of explicitly Christian faith, is nonetheless active in her heart and life? Is the good that Malala is doing simply a consequence of God’s common grace, but lacking the saving grace that’s necessary for her salvation? Is it more important that Malala continue her work for the rights of women to be educated, or for her to turn explicitly to Christianity — if it has to be one or the other?

A common refrain among pietistic Christians runs, “Only one life will soon be past; only what’s done for Christ will last.” This refrain is fine insofar as we’re talking about the real Christ who passes all boundaries and not a false Christ who insists on putting an explicitly Christian label on everything. Pietism, historically, was a reaction against a Protestantism that got cold and jaded. The original pietists had a fervency of heart in their devotion to Jesus and desire to help humanity. But all good things seem to get bent eventually. In the case of pietism, it became overly introspective and even self-indulgent in its promotion of personal piety.

Far too often, as Christians we get overly focused on wanting to see the Christian brand explicitly marked on the events of the world before we are willing to endorse them as good and done with God’s blessing. In the case of Malala, are we able to see her efforts (imperfect though they are) as for Christ and with God’s blessing even though she is a Muslim?

It seems to me as Christians we should be able to celebrate the good wherever we find it, and even without seeing an explicitly Christian label on the good we find. In the case of Malala, she would have been unable to accomplish what she did if she were not a Muslim because as a Christian, for instance, she would have had no standing in her community to support the right of Muslim girls to be educated.

In all these remarks, I don’t mean to take away anything from the Christian faith. I’ve read the Koran and I’ve read the Bible, and I much prefer the latter. But it seems that God moves where he wills, and our job is to follow God rather than to limit him by what we think he ought to do.

The thought of someone being saved at the moment of death raises an inverse possibility, namely, someone remaining a Christian up to the moment of death and thereupon renouncing the faith and going to hell (in those microseconds from fall to death). Some Christians hold to the perseverance of the saints or a once-saved-always-saved theology in which something like this could not happen — once you’re saved, you stay saved.

But for those who see salvation as potentially jeopardized by human free choice, this becomes a possibility as well. Catholic theology, for instance, teaches that a Catholic on the way to heaven can sin so grievously as to enter a state of mortal sin and thus be on one’s way to hell unless this state is reversed through confession and penance (Catholics contrast mortal sins with venial sins, venial sins being not so serious as to jeopardize one’s salvation). Personally, I would say that the mercy and grace of God precludes too much up-and-back/on-again-off-again between being on one’s way to heaven in the one case and hell in the other, but I raise such possibilities for completeness.

8. The Threat of Hell

The Catholic use of mortal sin to consign its members alternately to heaven or hell depending on whether they have repented or have yet to repent from such a sin raises the bigger question about the threat of hell generally. Let me set the stage autobiographically. My late father was raised during the Great Depression by a Polish Catholic mother in Chicago whose husband (my grandfather) had abandoned the family, which meant that my father from age seven was selling newspapers, later setting up pins in a bowling alley, etc. He was out and about, at times barely skirting the law, and he was no angel.

When he was still in his preteens, his mother would periodically be outraged about things he would do, crying out to him “that’s a mortal sin” and suggesting “you’re on your way to hell.” For a while, this used to get his attention and upset him, but, as he told me, eventually his reaction was just “Ahh, screw it.” (Actually, the language he used was more graphic, characteristic of the blue-collar Chicago neighborhood in which he grew up.)

Now there’s a semantically equivalent expression to describe his reaction, namely, “The hell with it.” This connection is interesting and perhaps not a linguistic coincidence. The threat of hell, when overused and giving people no hope of digging themselves out of the hole they’re in, thus gets used as a way of dismissing hell. It is a statement of abandonment.

We see this abandonment in many other contexts, as for instance when people who are obese try to lose weight but lose hope after repeated failures and thus give up trying to lose weight entirely, eating with abandon. We see this phenomenon even more extremely with opioid addiction, where every good thing in life is abandoned to prevent dopesickness.

The threat of hell thus seems to have limited effectiveness at positively motivating people and can even become a profoundly unhealthy motivator. Some sensitive souls may respond to this threat with a fear that doesn’t abate over time. But most people after a while find this threat cloying, dismissing not just hell but also Christianity in the process. (By the way, my dad, who would have been 100 this year, did turn to Christianity later in life, no thanks to my grandmother’s outrages over his “mortal sins.”)

In either case, however, I doubt that the threat of hell significantly reduces our rate of or propensity for sinning. Psychological studies reveal that a certain level of threat can be effective at controlling behavior provided the threat can be readily avoided and is not played up too dramatically. But threats posed in apocalyptic terms often end up constituting a siren call, tempting people, especially when the threat seems to pose no immediate danger.

Leaving aside who goes to hell, who doesn’t, and the precise nature of hell, it’s fair to say the threat of hell as an ethical motivator leaves much to be desired. Indeed, what sort of moral accomplishment is it to say “I really wanted to sin and would have sinned and still want to sin, but the fear of hell prevents me”?

Shouldn’t it be love of God and neighbor that motivates us and keeps us from sinning? And short of that, what about self-interest, to wit, the idea that sin will make life worse regardless of whether God adds punishment to it. On this view, sin, by being bad for us, is its own punishment. In this way, law becomes grace, telling us what not to do for our own benefit.

In this context, it’s also worth noting that very few people actually see themselves as on the way to hell. According to Pew Research, 72 percent of Americans believe in heaven, defined as a place “where people who have led good lives are eternally rewarded,” and only 58 percent believe in hell, defined as a place “where people who have led bad lives and die without being sorry are eternally punished.” Those numbers don’t go up dramatically for Christians. Even among evangelicals, just under 90 percent believe in heaven and just over 80 percent believe in hell.

For even starker percentages, however, consider that according to a Barna poll about two-thirds of Americans think they’ll end up in heaven but only half of one percent think they’ll end up in hell (leaving the rest, presumably, unsure about their eternal destiny). That only half of a percent of the population thinks it is actually going to hell is remarkable, but perhaps unsurprising. We overwhelmingly, it seems, rationalize the evil in our hearts. Consider the following opening to one of the most popular books of the 20th century, Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People:

When [the notorious criminal Francis] Crowley was captured, Police Commissioner E. P. Mulrooney declared that the two-gun desperado was one of the most dangerous criminals ever encountered in the history of New York. “He will kill,” said the Commissioner, “at the drop of a feather.”

But how did “Two Gun” Crowley regard himself? We know, because while the police were firing into his apartment, he wrote a letter addressed “To whom it may concern.” And, as he wrote, the blood flowing from his wounds left a crimson trail on the paper. In his letter Crowley said: “Under my coat is a weary heart, but a kind one — one that would do nobody any harm.”

A short time before this, Crowley had been having a necking party with his girl friend on a country road out on Long Island. Suddenly a policeman walked up to the car and said: “Let me see your license.”

Without saying a word, Crowley drew his gun and cut the policeman down with a shower of lead. As the dying officer fell, Crowley leaped out of the car, grabbed the officer’s revolver, and fired another bullet into the prostrate body. And that was the killer who said: “Under my coat is a weary heart, but a kind one — one that would do nobody any harm.”

Crowley was sentenced to the electric chair. When he arrived at the death house in Sing Sing, did he say, “This is what I get for killing people”? No, he said: “This is what I get for defending myself.”

The point of the story is this: “Two Gun” Crowley didn’t blame himself for anything.

Is that an unusual attitude among criminals? If you think so, listen to this: “I have spent the best years of my life giving people the lighter pleasures, helping them have a good time, and all I get is abuse, the existence of a hunted man.”

That’s Al Capone speaking. [Compare Tony in The Sopranos.] Yes, America’s most notorious Public Enemy — the most sinister gang leader who ever shot up Chicago. Capone didn’t condemn himself. He actually regarded himself as a public benefactor — an unappreciated and misunderstood public benefactor.

Carnegie uses this self-(mis)understanding of criminals to advocate for his doctrine of non-criticism and approbation (i.e., if you’re going to work effectively with people, don’t criticize them but focus on their positive points where you can offer genuine appreciation). In any case, the half of one percent statistic of people who think they’re actually on their way to hell should really be quite shocking to those pushing the extreme view of hell described earlier, who are ready to consign to hell any adults with normal cognitive function who have not explicitly acknowledged Christ as their savior.

Apparently, the truth about hell is simply not getting out. Indeed, well over half the world’s population is, according to the extreme view, on their way to hell, having failed to acknowledge Jesus. Yet, they are either ignorant of this threat or unimpressed by it (assuming Barna’s numbers for the U.S. can be extrapolated worldwide, which doesn’t seem unreasonable).

What a strange thing. If hell were really that big a threat, wouldn’t it be best to have some sort of window or portal onto eternity that everyone could access and confirm for themselves just how bad hell is and how much they should try to steer clear of it? “Hey, there’s Uncle Frank. He always was a nasty piece of work. Look at him there just screaming and shrieking and being tormented with unspeakable pain. I’m sure not going to follow in his footsteps.”

But we don’t have anything like that, not in this life. According to Thomas Aquinas, in an earlier quote, the saved will witness the torments of the damned in order to better appreciate the blessings of heaven. But while still living on earth, we seem to be denied convincing access to the torments of hell’s inhabitants, which might render the threat of hell more effective at producing right action.

Comment: What if Thomas was wrong about the saved witnessing the sufferings of the damned in hell to make their joy of heaven complete? What if, instead, the saved are so consumed with the joys of heaven that they ignore the damned in hell, and rather, the sufferings of the damned consist in watching the saved in heaven so enjoying themselves that they regret that they’re not there to enjoy heaven with them? In other words, hell watches heaven rather than the other way round. Accordingly, the torment of hell would consist not in being actively tortured but in the consciousness that its inhabitants have missed out on their greatest happiness.

Perhaps I’ve understated the efficacy of hell as a deterrent to sin and as a motivator of right action. Even though we have no window on hell itself, we have windows on the difficulties humans experience in consequence of bad decisions. Unbridled sexual activity, for instance, tends to produce STDs with all their attendant distress. Unbridled alcohol consumption likewise invites pain and misery.

In such cases, the act produces its own negative consequences. Is it possible that this is the closest thing we have to a window on hell? If so, this would suggest that hell is a natural consequence of a life lived in opposition to God rather than a punishment that God inflicts as a way of exacting vengeance. We’ll return to this possibility in due course.

9. Hope vs. Total Certainty of Salvation

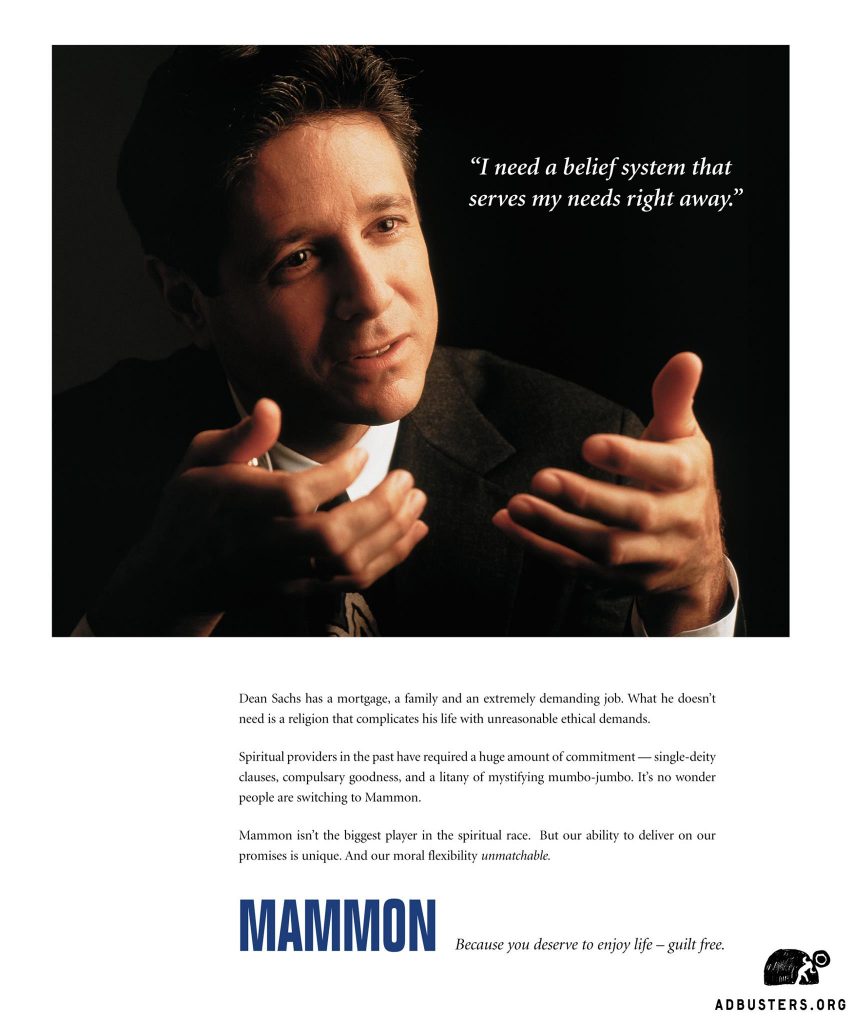

An approach to evangelism from a few decades back known as Evangelism Explosion used as its starting point the question “If you were to die today, would you go to heaven?” When asked this question, a lot of people respond with a tentative “I hope so” and yet take the optimistic view that they’re likely go to heaven because their good works outweigh the bad. But for the purveyors of Evangelism Explosion, that wasn’t good enough. The conservative theology behind this evangelization program demanded not mere hope or probability of making it to heaven but certainty.

An approach to evangelism from a few decades back known as Evangelism Explosion used as its starting point the question “If you were to die today, would you go to heaven?” When asked this question, a lot of people respond with a tentative “I hope so” and yet take the optimistic view that they’re likely go to heaven because their good works outweigh the bad. But for the purveyors of Evangelism Explosion, that wasn’t good enough. The conservative theology behind this evangelization program demanded not mere hope or probability of making it to heaven but certainty.

Now certainty is a great thing if you can have it, but is anyone really entitled to say “I’m sure I’ll end up in heaven,” or for that matter “I’m sure I’ll end up in hell”? The Protestant preoccupation with certainty or assurance of salvation, which is very much in evidence among present-day Evangelicals, goes right back to the start of Protestantism, beginning with Martin Luther’s scrupulosity about his own sin, always second-guessing himself, and never finding solace in the Catholic rites of confession and penance. His breakthrough came in reading the Apostle Paul and his teachings about being saved by faith through grace. Ah, here was the release Luther was looking for. Because he had faith, he could be assured that he was saved and on his way to heaven.

But is anyone really warranted in having such total assurance of going to heaven? Is it even a good thing to have such assurance? It’s interesting to me, as a philosopher, to see, around the time of the Reformation, philosophy taking an epistemological turn that emphasized how we come to know and how we can have knowledge that is sure and certain (Descartes, who came a few generations after Luther exemplified this approach to philosophy–cf. his cogito ergo sum, in which he found total certainty in his existence based on his capacity to think).

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t have a problem with the quiet confidence of feeling right with God and believing that one is on one’s way to heaven. If such a person is asked whether he or she is going to heaven, a response like “I hope in salvation” or “I have confidence in God’s faithfulness to save me” seems entirely appropriate and winsomely humble. But anything much beyond that strikes me as presumptuous.

Do you have the inner witness of the Spirit assuring you, with complete certainty, that you’re on your way to heaven? Well, lots of people have claimed as much and ended up with shipwrecked faith. Are you impervious to temptation? Are there no circumstances that can draw you away from Christ? At such points, we are likely to recite Romans 8:37–39, which runs through the gamut of life’s challenges, and promises that these are unable to separate us from the love of Christ. The one challenge that’s unmentioned in this list, however, is our own volition in turning away from Christ.

I don’t mean to create doubts about people’s salvation simply for the purpose of creating doubts. Indeed, I’m not creating doubts at all. It is the apostles of certainty who create doubts by insisting on such overconfidence toward salvation that they actually end up undermining a true confidence in salvation.

Consider that when Jesus was at the Last Supper and remarked that someone at the table would betray him, all the disciples (and not just Judas, the intended target) asked the question “Is it I?” Now why would they do that if they were totally certain of their faithfulness to Christ and thus of their salvation? Oh, there was one exception: “If all the others betray you, I never will.” That was Peter, and we all know how successful he was at fulfilling his promise, denying Christ three times.

Okay, but that was before the cross, the resurrection, and the infilling of the Holy Spirit after Pentecost. And the disciples’ concern at the Last Supper was merely about betraying Jesus, not their ultimate salvation (is there a difference?). With the birth of the Church (capital “C”) after Pentecost, however, things would be different, right? Now Christians could boast of 100 percent assurance in their salvation. But what then do you do about Paul’s farewell address to the Ephesian Christian leaders in Acts 20:25–30:

Now I know that none of you among whom I have gone about preaching the kingdom will ever see me again. Therefore, I declare to you today that I am innocent of the blood of any of you. For I have not hesitated to proclaim to you the whole will of God. Keep watch over yourselves and all the flock of which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers. Be shepherds of the church of God, which he bought with his own blood. I know that after I leave, savage wolves will come in among you and will not spare the flock. Even from your own number men will arise and distort the truth in order to draw away disciples after them.