Most books on miracles reach one of three conclusions: Miracles happen. Miracles don’t happen. Miracles can’t happen.

This book takes a different tack. Rather than settle the existence or nonexistence of miracles, we ask why we’re talking about miracles in the first place. Why do we make such a big deal about them? What makes them an endless topic of debate? If miracles do indeed happen, why isn’t the evidence for them more convincing and obvious? If miracles don’t happen, why isn’t their absence equally convincing and obvious?

Miracles are neither like horses nor like unicorns. Horses have made themselves so clearly evident that no one can deny their existence. Unicorns have hidden themselves so well that no one is justified asserting their existence. Miracles occupy a middle ground that gives reasons to think that they exist but also raises doubts to question whether they exist.

Miracles cannot be dismissed as the ravings of an unhinged or uneducated or unscientific fringe. Many normal, feet-on-the-ground, well-informed people believe that they or their loved ones have personally experienced a miracle, that they have good reasons for believing in miracles, and that miracles play an important role in the world.

As just one of countless examples, take Nobel laureate writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s description of his cure from cancer while a prisoner in the Soviet Gulag:

In autumn 1953 it looked very much as though I had only a few months to live. In December the doctors—comrades in exile—confirmed that I had only three weeks left… I did not die, however. With a hopelessly neglected and acutely malignant tumor, this was a divine miracle. I could see no other explanation. Since then, all the life that has been given back to me has not been mine in the full sense: it is built around a purpose. [Solzhenitsyn 1975, pp. 3-4]

Solzhenitsyn lived another fifty-five years.

Despite such widespread accounts of miracles, many people remain skeptical about miracles, thinking that most, or even all, miracle claims fall apart on closer examination. Who’s to say that Solzhenitsyn’s cancer was as advanced or serious as he claims? Medical care in the Soviet Gulag was minimal at best. No official medical records of his cancer survive, to say nothing of X-rays or hard evidence. Too often, the credibility of miracles depends entirely on human testimony, with its biases, and lacks scientific evidence, with its rigor.

Yet even scientific evidence of miracles, when it exists, can fail to convince. James Randi, for instance, is a noted skeptic and debunker of the paranormal. He has offered cash prizes to anyone who can prove a miracle. Yet no supposed miracle to cross his path has ever, in his view, merited a cash prize. Randi is aware of “spontaneous remissions” of diseases, in which people experience remarkable recoveries unexplained by medical science. But they cut no ice with Randi.

Such occurrences, rare though they are, provide good scientific evidence that certain people have been suddenly and inexplicably cured of their diseases. Randi will readily admit that such cures have occurred. But he then denies that they are miracles. As he puts it, “one by one … these spontaneous remissions from things like cancer will be explained eventually. We just don’t have the explanation at this point. But that doesn’t mean they are miraculous.” [2011 interview with James Randi at Superscholar.org] In other words, an ordinary explanation acceptable to the most hard-nosed skeptic is sure to exist for every supposed miracle, but for now we just don’t know enough to say what it is.

***

To talk about being either convinced of miracles or skeptical about them presupposes a prior question: what do we even mean by miracles? Work on this book started when the authors contacted a well-known survey company to conduct a scientific poll of people’s attitudes toward miracles. We were prepared to spend a significant amount of cash to conduct such a poll. We wanted to understand not so much whether people believe miracles happen but the significance of miracles in their lives and thought. Even professional skeptics who debunk miracles for a living find them important (the empty set can nonetheless be an interesting set!).

After going round and round with the survey company, we did converge on a list of questions on which we could all agree (included as a chapter in this book, along with a discussion of its significance). But we could never agree on the definition of miracles. The definition that we, the authors of this book, thought best focused not just on the extraordinariness of miracles but also on their supposed supernatural source: “a miracle is an event or act that defies ordinary explanation and whose occurrence seems to require some influence or power outside nature.”

The survey company insisted that we limit the definition of miracle to events without ordinary explanation, omitting any reference to the supernatural. This, it seemed to us, missed the point of miracles, namely, that they are not just wildly unexpected events, but also experienced by people as a sign of divine or supernatural influence (like Solzhenitsyn above), pointing beyond a material world otherwise ruled by unbroken natural law. To understand miracles as we proposed and to accept that they exist then means that the natural world cannot be a closed system of natural causes but rather must be an open system that can accommodate causes beyond nature. Miracles, if real, can therefore never be explained in ordinary naturalistic terms or duplicated by scientific experiments that rely on natural law.

In the end, we decided to conduct our own “unscientific” poll of people’s attitudes toward miracles using the survey we had constructed in discussions with the survey company. Who knows, we may yet conduct a scientific poll with this company (we parted on friendly terms), but our findings from the unscientific poll, which we uploaded onto a popular educational website, were nonetheless revealing. Supplementing these poll results with extensive research and interviews has given us a wealth of insights into the range of attitudes toward miracles that people entertain.

The Faces of Miracles is a work of clarification rather than persuasion. If at the end of this book readers better understand the impact of miracles on people’s lives, we will consider this book a success. We have tried to provide a representative cross-section of views on miracles. But we have made no attempt to be encyclopedic. The people whose views on miracles we examine are almost exclusively from the English-speaking world, contemporary or fairly recent, and either Christian or reacting to Christianity (as when a skeptic debunks Christianity for its reliance on miracles). And even within Christianity, we’ve tended to focus on that segment of Christianity we know best, namely, Protestant and Evangelical.

Of course, miracles are not limited to Christians or Christianity. Indeed, accounts of miracles have been reported across the world and across faiths. But a book like this could easily have mushroomed if we also considered miracles outside the Christian context. Yes, it would have been interesting to cast the net wider to include such miracle workers as Brazil’s John of God and India’s late Sai Baba. But the supernatural power ascribed to them takes many of the same forms, at least in outward expression, as seen with the Christian faith healers we consider, even if the ultimate source of the healing power is understood differently. Accounts of miracles show common patterns, and those patterns are exemplified in this book. We therefore didn’t think we lost much by focusing on the Christian context.

To put our cards on the table, both authors are Christians and believe in miracles. But we also think that belief in miracles is never mandated: one can always find reasons, and not just spurious reasons, to deny that an event is a miracle, and thus to refuse to attribute the event to a supernatural cause. The atheist philosopher Norwood Russell Hanson, for instance, declared that he would be converted to theism if he experienced the following miracle:

The heavens open, and the clouds pull apart, revealing an unbelievably radiant and immense Zeus-like figure towering over us like a hundred Everests. He frowns darkly as lightning plays over the features of his Michelangeloid face, and then he points down, at me, and explains for every man, woman and child to hear: “I’ve had quite enough of your too-clever logic chopping and word-watching in matters of theology. Be assured Norwood Russell Hanson, that I do most certainly exist!” [Hanson 1971, pp. 313–14]

But would the occurrence of such an extraordinary event truly have convinced Hanson that God exists? No doubt, Hanson would consider the experience of such an event remarkable. But alternative naturalistic explanations, such as aliens or hallucinations, would also occur to him, especially given his atheist presuppositions. Remarking on the importance of prior background beliefs in determining whether we accept or reject miracles, C. S. Lewis noted that he knew one, and only one, person who was convinced that she had seen a ghost, and yet this person didn’t believe in ghosts, not even after the experience. [Lewis, p. 1]

The French skeptic Anatole France, in his book The Garden of Epicurus, described his visit to Lourdes, the French shrine where many people claim they were miraculously healed (see chapter 10). He notes that visitors to Lourdes left behind many crutches, thus testifying that they had experienced miraculous healing in their legs. But he then asked why no wooden legs were left behind. Is God unable to heal amputees? Indeed, no amputees are known to have been healed at Lourdes.

But even if an amputee had been healed at Lourdes, Anatole France would refuse to admit that a miracle had occurred. As he put it:

Speaking philosophically, the wooden leg would be no whit more convincing than a crutch. If an observer of a genuinely scientific spirit were called upon to verify that a man’s leg, after amputation, had suddenly grown again as before, whether in a miraculous pool or anywhere else, he would not cry : “Lo! a miracle.” He would say this: “An observation, so far unique, points us to a presumption that under conditions still undetermined, the tissues of a human leg have the property of reorganizing themselves like a crab’s or lobster’s claws and a lizard’s tail, but much more rapidly.” [France 1908, pp. 176–177]

Let this statement sink in. It shows that no evidence could ever induce a thorough-going skeptic, like Anatole France, to admit that a miracle had indeed occurred. In every case, skeptics can cite the possibility of alternative naturalistic explanations. Accordingly, even if no clearly defined naturalistic explanation is on hand, skeptics can rationalize that no actual miracle has occurred, preferring instead simply to believe that we are for now ignorant of the underlying naturalistic causes. James Randi’s remarks earlier on spontaneous remissions took exactly the same skeptical approach to miracles. By presupposing that miracles cannot happen, such skeptics are unlikely to change their views about miracles no matter what the evidence.

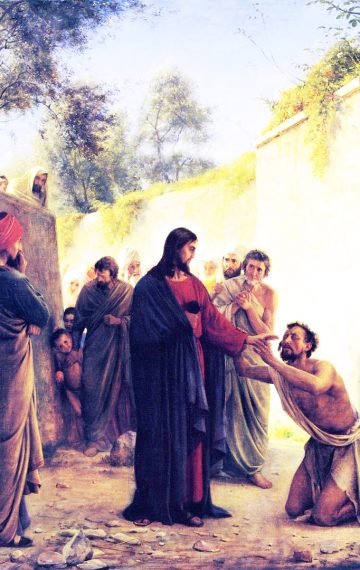

Conveniently, Anatole France did not have to deal with anything so flamboyant as amputees being healed but instead with tamer purported miracles, like people simply being able to put away their crutches. Even in the Bible, no case is recorded of an amputee receiving back a lost limb. The case of the high priest’s servant, whose ear Peter cut off in the Garden of Gethsemane, comes closest to Jesus healing an amputee (see Luke 22:50–51). But even here, Jesus did not make a new ear grow from scratch, but rather reattached the old ear (which is what doctors do today with severed body parts).

The only widely discussed case of an amputee regaining a severed limb is the famous seventeenth century Miracle of Calanda, in which a Spanish peasant named Miguel-Juan Pellicer had his leg amputated in 1637 and then, while sleeping, is said to have miraculously recovered it in 1640. Interestingly, the new leg seemed identical to the one lost, having the same scars. Moreover, the place in the hospital cemetery where the old leg had been buried was found empty. So was this a case of a completely new leg growing back or of an old leg being resurrected and reattached? Was this a true miracle at all? [For an account of the Miracle of Calanda, see Clairval.com. For a skeptical response, see Skeptoid.com.]

Even to raise such questions is to raise doubts about this miracle. And indeed, doubts can be raised about any purported miracle. Miracles, should they happen, tend not to be over-obvious. If they are believed, it is often for personal rather than purely rational reasons, because the miraculous event fits meaningfully with a person’s life and not because it would convince any and all comers. Solzhenitsyn again: “Since then [i.e., since his miraculous healing from cancer], all the life that has been given back to me has not been mine in the full sense: it is built around a purpose.”

One of us (BD) recalls visiting a large charismatic church in Korea. The church owned a property by a lake, and I was told the head pastor was preparing himself spiritually in order to walk on that lake so that, with television crews on hand, this miracle could be covered on national television and provide proof positive of God’s power on earth. That was almost two decades ago, and the miracle has yet to happen. Perhaps if CNN had film crews out in Jesus’ day, they could have captured slam-dunk evidence of his miracles. But in our day slam-dunk miracles never quite seem to materialize.

***

Despite the absence of incontrovertible miracles that would convince all comers, remarkable events that defy ordinary explanation and lead people to see a supernatural hand are widely reported and believed. Even skeptics will admit an uncanniness to the coincidental timing of certain events, rendering miracles plausible even if the skeptics themselves remain personally reluctant to embrace a supernatural worldview. Take skeptic Michael Shermer’s article in Scientific American about an unusual event that took place on his wedding day. Shermer titled the article “Anomalous Events That Can Shake One’s Skepticism to the Core,” and subtitled it “I just witnessed an event so mysterious that it shook my skepticism.”

What was the event? On Shermer’s wedding day to Jennifer Graf in 2014, the two of them witnessed her dead grandfather Walter’s 1978 Philips 070 transistor radio suddenly came to life, after not working for many years. Jennifer desperately missed Walter, who was closest to a father figure when she was growing up. On their wedding day, sounds of music in Michael and Jennifer’s home led them to a desk drawer where Jennifer “pulled out her grandfather’s transistor radio, out of which a romantic love song wafted. We sat in stunned silence for minutes. ‘My grandfather is here with us,’ Jennifer said, tearfully. ‘I’m not alone.’” After the wedding day, the radio never worked again.

Shermer then asks how to make sense of this event. He starts by half-heartedly invoking the high probability of anomalous coincidences when considered in light of the vastly many events people experience. But then he adds, “Jennifer is as skeptical as I am when it comes to paranormal and supernatural phenomena. Yet the eerie conjunction of these deeply evocative events gave her the distinct feeling that her grandfather was there and that the music was his gift of approval. I have to admit, it rocked me back on my heels and shook my skepticism to its core as well. I savored the experience more than the explanation.” [Quoted from his Scientific American article.]

Shermer, nonetheless, continues to affirm his skepticism and refuses to ascribe this event to a supernatural cause. He therefore denies that it is a miracle in the sense defined in this book. And yet, given how this event shook his skepticism, Shermer would be hard pressed to deny that others might legitimately interpret this event as a miracle. That’s what his wife Jennifer did, at least initially, when she ascribed the event to her departed grandfather’s presence.

A common objection by skeptics against miracles is that strange connections among events, such as the one that shook Shermer’s skepticism, are in fact highly probable once we factor in all the events that happen that don’t draw our attention. The late skeptic Martin Gardner put it this way: “The number of events in which you participate for a month, or even a week, is so huge that the probability of noticing a startling correlation is quite high, especially if you keep a sharp outlook.” [Gardner, work cited in references below]

But in fact, we often have no way to calculate the probability or improbability of startling correlations. Moreover, some improbabilities might be so extreme that no number of events in which humans have participated throughout history could raise the probability enough to make certain events seem plausible. Take 100 heads in a row with a fair coin, an event of probability one in a million trillion trillion (by comparison, there are fewer than a billion billion grains of sand on the earth). If all humans throughout history spent their time on nothing but flipping coins, it would still be vastly improbable that any one of them would ever witness 100 heads in a row.

How improbable does a coincidence have to be before it becomes a miracle? Several decades ago, one of us (BD) experienced a coincidence even stranger, in my view, than the one recounted by Shermer. I was taking a year off from school working in the family business. My late mother was an art dealer who specialized in 19th and early 20th century American and European oil paintings. Within a few months, she was offered virtually identical paintings by a famous Austrian artist (Franz von Defregger). The paintings had the same dimensions, subject, and price. Both were overpainted prints, and so both were fakes.

The first was offered from Melbourne, Australia, the second from Melbourne, Florida (the sellers were completely independent). Unfortunately, my mother paid for the fake from Australia and lost a lot of money on it (years of litigation failed to recover anything). My mother did not buy the other fake, but the people in Florida selling it had another painting by a famous Munich artist (Heinrich von Zügel), which my mother bought, and on which she more than recouped the loss to Australia.

More significant than the multiple coincidences in this story is that it occurred at a crucial point in the life of my family, just as the mysterious radio coming to life happened at crucial time in the life of Michael Shermer and Jennifer Graf when they were getting married. Right between the loss to Melbourne, Australia and the recovery from Melbourne, Florida, my mother was becoming a Christian, embracing a newfound faith and encouraging my father and me to do the same (he and I became Christians a few months later). It was as though in this “miraculous” set of coincidences, God was providentially telling our family that he holds our lives in his hands and has the power to turn circumstances around on a dime. My parents (now both dead) and I always accepted this interpretation, regarding what happened as a miracle.

So was it really a miracle? If by “really a miracle” one means an event that would convince any and all comers of its supernatural source, obviously no. Skeptics will find plenty with which to cavil in this story. But skeptics always find something with which to cavil (it’s their job). Yet no amount of skeptical cavilling would have convinced my family that this was not a miracle. We experienced an overwhelming visceral immediacy as this story unfolded (the loss to Melbourne, Australia was particularly painful), which made any after-the-fact naturalistic rationalizations of what happened seem hollow. The proverb that says “someone with an experience is never at the mercy of someone with an argument” held true for us in this case.

***

The danger that skepticism always faces is throwing out the baby with the bathwater, in this case utterly rejecting miracles even when there might be good evidence for them. Nonetheless, skepticism has an important place in the discussion of miracles. Even if skepticism cannot disprove all miracles, it can legitimately disprove some. A lot of supposed miracles are frauds, and the skeptic does valuable service as a debunker of fraudulent miracles.

Take the case of Peter Popoff, the fraudulent faith healer that James Randi exposed in the mid 1980s. Popoff was popular at the time, pulling in millions of dollars annually by convincing gullible people that he was God’s instrument to bring about their miraculous healing. Popoff’s real secret? He would send shills into an audience asking questions and gathering information. Then, come showtime, Popoff would mingle with the audience, exhibiting an uncanny knowledge about audience member’s lives, proclaiming their miraculous healing and deliverance.

Randi, attending Popoff’s healing rallies, thought it unusual that Popoff would be wearing what looked like a hearing aid: why would a faith healer who touts God’s power to heal advertise being hard of hearing? So Randi and his team investigated and found that Popoff’s earpiece was in fact a radio receiver used by his wife, who read to him the names, addresses, and infirmities of audience members previously pumped for information by Popoff’s shills. Randi performed a great public service by exposing Popoff, which had the effect of bankrupting his ministry (for more details about the Popoff case, see the chapter in this book about James Randi).

The fraud in the Popoff case was extreme. Yet in many accounts of miracles, fraud can safely be ruled out. In the story of the two Melbournes, the only fraud was in the fake paintings. With the two Melbournes, my family experienced a deeply meaningful coincidence (much like Shermer’s wife Jennifer Graf did over the old radio), and ever after we saw a supernatural or miraculous hand in it. It’s not that we had to strain to believe a miracle. We believed it, and it didn’t matter to us whether others interpreted it as a miracle. It was enough that we were convinced.

Of course, people can be mistaken about miracles for reasons other than fraud. Another reason is self-deception, prompted perhaps by a desperate need to believe in a miracle as a last resort. And then there’s ignorance of underlying natural causes, if indeed there is an underlying naturalistic explanation. Skeptics like James Randi and Anatole France embrace a naturalistic worldview that makes miracles impossible and guarantees an underlying naturalistic explanation must always exist (if we could but know it).

They may be right that supernatural explanations will in the end always give way to natural explanations. But if they are right, how can we know that? And if they are wrong, how can we know that? And what if no side in this debate is ever able to mount an airtight case one way or the other? Because such questions show no sign of being resolved, a wide ranging and open conversation seems the best we can do to attain a genuine understanding of miracles. The Faces of Miracles is such a conversation.

***

A prime reason that miracles are not universally convincing is that they tend to reside in a sweet spot or Goldilocks zone: not too little, not too much, just right. It’s not that a supposed miracle is so ordinary an event that it doesn’t capture our imagination (i.e., too little). It’s not that a miracle is so overpowering that it instantly overturns the worldview of skeptics (i.e., too much). It’s that a miracle is at once extraordinary but also deeply meaningful to the party directly experiencing it, enough to elicit faith in an underlying supernatural source, but not to compel faith (i.e., just right).

Why aren’t miracles more overpoweringly obvious? One reason may be that humans are amazingly adaptable. What’s an extreme miracle today won’t seem extreme tomorrow. What was overpowering yesterday quickly becomes the new normal. Thus raising the baseline for miracles, even to new extreme levels, won’t convince skeptics any more than the current tamer stock of miracles. Recall that Anatole France would have regarded amputees receiving new limbs as unmiraculous. Rather, he would have concluded that “under conditions still undetermined, the tissues of a human leg have the property of reorganizing themselves like a crab’s or lobster’s claws and a lizard’s tail.”

Another reason why miracles may not be more overpoweringly obvious is that it is in humanity’s best interests to keep them somewhat muted. The desire for miracles can become addictive, requiring miracles of ever greater intensity to experience the same “rush” (witness the Israelites under Moses departing Egypt: according to the story, they kept witnessing greater and greater miracles, and yet were never satisfied). Moreover, the refusal to see something as a miracle is often less intellectual than moral. We ought to believe what we’ve been given enough evidence to believe. But to insist on overwhelming evidence quickly becomes unreasonable, inviting skeptics to keep raising the bar higher and higher.

The atheist philosopher Bertrand Russell was questioned what he would say to God if, after dying, he met God and were asked why he hadn’t believed in God during his time on earth. Russell is said to have answered, “Not enough evidence.” So, if only God had provided enough evidence in support of theism, Russell would have been a theist? [This quote is widely available on the Internet, and Richard Dawkins attributes it to Russell is on page 104 of his book The God Delusion (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006). But neither Dawkins nor the Internet sources we’ve found that list the quote provide a reference to Russell’s actual writings. Still, we can well imagine Russell saying just this.]

But what is enough evidence? And, at an even more basic level, what makes something to be evidence, supporting a claim or failing to support it? The problem with evidence is that it is not, and indeed cannot be, decided by evidence. Like the eye that cannot see itself, so evidence cannot see itself as evidence. Indeed, what determines whether something counts as evidence depends on what we, as human inquirers, are predisposed to take as evidence. And what if we, because of our naturalistic worldview, are predisposed to take nothing as evidence for miracles, like James Randi and Anatole France?

Or what if we employ a double standard for evidence, accepting some things on minimal grounds but then, when it comes to miracles, raising the bar so high that nothing can count as evidence? This was philosopher David Hume’s objection to miracles, arguing that we should always discount the testimony of miracles in the face of the low prior probability of miracles. But where did he get that low prior probability? Philosopher John Earman, himself an atheist, has debunked Hume’s argument, showing it to depend on a faulty conception of probability. [See Earman book cited below.] But the animating impulse behind Hume’s objection, which is to deny that miracles can have any legitimate evidence in their favor, remains.

If God is the ultimate source behind miracles, and if through miracles God attempts to communicate with humans, then God’s job is not to regale us with a freak show of spectacular sights but rather to get our attention and focus it in ways that make the world a better place (a world that desperately needs improvement because it is filled with moral and natural evil). In particular, humans do not become better humans, and thus do not make the world a better place, because God provides such overwhelming evidence of miracles that they feel compelled to be good. Thus, even Judas did not feel compelled to be good, instead thinking he could betray Jesus with impunity, the very Jesus he had seen daily and who is regarded as the greatest miracle-worker in history.

The potentially dizzying effect of miracles on the miracle worker may impose another limitation on miracles: perhaps God is protecting us from the hubris that thinks we mere humans can produce miracles at will. Miracle workers can easily get full of themselves; after all, a supernatural source appears to be using them as a channel for miracles. That’s heady stuff, and it tends to go to their heads.

I (BD) recall in 1979 being at miracle rally of the late R.W. Schambach. I personally did not witness any notable miracle at this rally. Yet at the rally, Schambach claimed, without offering details about time and place, that he had gone to a hospital wing in some developing country and cleared out from that wing all its sick patients by successfully praying for their healing. Even for those whose worldview allows for miracles, Schambach’s claim to have cleared out a hospital wing will seem farfetched.

It’s worth putting such grandiose claims (and faith healers are notorious for grandiose claims) in perspective. Jesus himself didn’t perform miracles indiscriminately. For instance, the fifth chapter of John’s Gospel describes the Pool of Bethesda where a “great multitude” of sick people lay, waiting for a miraculous stirring of the water by an angel, so that the first person to enter the pool, once stirred, got healed. Jesus, visiting the pool, chose one person to heal, and he did it on the Sabbath, getting himself in trouble with the authorities. Why didn’t Jesus clear everyone out at the Pool of Bethesda, healing all the sick people there, as Schambach claims to have done at that undisclosed hospital wing?

Or consider the healing of the lame man by Peter described in Acts 3. Jesus had by this time been crucified and resurrected, so he was no longer physically present. It was therefore up to his disciple Peter to heal this man. Who was this man? According to Acts 3:2, he “was lame from his mother’s womb” and needed to be “laid daily at the gate of the temple which is called Beautiful, to ask alms of them that entered into the temple.” But think what this means. Jesus had for years been going to the Jerusalem temple. He must surely have seen this man, and not once but repeatedly. Why, then, didn’t Jesus heal him when he had the chance?

***

Paradox and puzzlement often accompany miracles. Not only do purported miracles tend not to be overobvious, but their timing and connection to other related events often makes little logical sense. If miracle A happens, we might expect miracle B also to happen. But such correlations are often absent. Take Demos Shakarian, a well known charismatic leader from a generation back. He saw his mother die of an inoperable cancer but his sister healed from a horrendous car accident. It’s more satisfying to the mind, which yearns for consistency, to see neither miraculously healed or both miraculously healed. But why one and not the other? Miracles seem to occur selectively, and often with no rhyme or reason. [See Shakarian reference below.]

The lack of discernible patterns in situations where miracles occur or ought to occur is striking. It’s as though God, if God is indeed the source of genuine miracles, were nonetheless intent on shielding witnesses of miracles from the underlying divine motivations for them. From miracles witnessed in the past we seem to derive no clear understanding of the time, place, person, or method yielding the next miracle.

Why? Perhaps, as suggested earlier, miracles, as exhibitions of divine power, may simply present too great a temptation for humans, who might otherwise too readily ascribe the power for bringing about miracles not to God but to themselves (and that despite all the usual disclaimers and protestations by faith healers that it is God and not the faith healer who does the healing). Or perhaps miracles, as acts by a sovereign God, follow patterns that are necessarily inscrutable to us given our limited perspectives and intellects.

One of us (BD) attended a Templeton Foundation conference at MIT back in the late 1990s at which the leading light in the hospice movement, Dame Cicely Saunders, spoke. Her work underscored the need for palliative care with patients close to death (for this work she received the Templeton Prize in 1981 — note that two years later in 1983 Solzhenitsyn also received the Templeton Prize). When I sat with her over a meal, I asked if in all her vast experience with dying patients she had ever witnessed one that was cured. She knew of only one case, a younger woman with a cancer who left hospice care by getting better, though Dame Saunders added that after a few years this young woman returned to hospice care and then did succumb to cancer (so she may well never have been properly cured). What better place to see miracles of dramatic healing than in a hospice setting? And yet Dame Cicely Saunders, the person in the best position to witness such miracles, didn’t see them.

Miracles can also seem inappropriate and unfair. Why does one person receive a needed miracle but not someone with an even greater need? And why do some miracles seem so trivial, especially against the backdrop of horrendous evil in the world? Sure, Solzhenitsyn getting cured of stage-four cancer in the Soviet Gulag seems like a worthy miracle. But miracles with a far greater reach and doing far more good are easily imagined. What about the miraculous deliverance of myriad torture victims from the hands of their tormentors, to say nothing of the miraculous alleviation of a famine by manna from heaven? Yet miracles, at least in our day, don’t seem to reach quite that far.

On the other hand, what are we to make of Michael Shermer and his wife hearing romantic music from a defunct radio? Or my (BD’s) family losing money on one art deal only to regain it, by strange coincidence and with interest, on another? Against the grand scheme of things, such miracles seem hardly momentous. From my present vantage, I (BD) would much prefer to swap miracles, seeing a complete loss of money in those past art deals, but seeing my severely autistic son (now 16 years into his disability) miraculously cured. Alas, miracle swaps like this are not an option.

The inequities that surround miracles may be there to remind us that the ultimate source behind miracles (God, for most of us) cedes little if any control over them to us. One sees this lack of human control over miracles in the otherwise ordinary lives of many faith healers, who in themselves and their families exhibit the same frailties, sicknesses, and tragedies common to humanity. Indeed, those who claim to be channels for miracles display limited success at resolving their own problems through miracles. For instance, healing missionary John G. Lake, six months after arriving in Africa, saw his wife die; faith healer Smith Wigglesworth did his healing crusades assisted by his deaf daughter; Oral Roberts was freed to pursue his healing ministry once his disabled sister died (he also saw two of his own children die, one in an airplane crash, the other by suicide).

***

One final point worth pondering before we end this introduction is how belief in miracles correlates with mental health. We submit—based on our experience, though without scientific proof—that an optimistic openness to miracles is good for one’s mental health. In general, confidence and optimism tend to be good for people, even if these are not totally realistic, because they keep us engaged in life and looking for solutions. So too, an openness to miracles can push us outside the box and help us meet grave challenges in novel ways, even if at the end of the day no miracle occurs.

Yet if an optimistic openness to miracles is healthy, we also find another attitude toward miracles that is unhealthy. Call it a relentless insistence on miracles or an unwillingness to accept life in the absence of miracles. Some of life’s challenges are so severe and intractable that barring a miracle, the challenges will persist and profoundly burden, or even end, people’s lives (think of a stage-four cancer or a chronic disability). If confronted with such a challenge, it’s one thing to be open to miracles. But it’s quite another to chase relentlessly after miracles, not resting content unless a miracle is received, and refusing to make peace with the challenge otherwise. This is bad. The secret to life is playing the hand you’re dealt, and when belief in miracles turns into an uncompromising demand for miracles, you effectively refuse to play the hand you’re dealt.

Psychiatrist Elizabeth Kübler-Ross described five stages of grief that arise when people must deal with a severe challenge. According to her, these stages occur in the following order: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and finally acceptance. Anyone who relentlessly insists that the only way to meet a life challenge is for a miracle to occur stays stuck at the denial stage. Because miracles are rare (if they were common, they would not be miracles), and because they seem to become rarer still when people insist on them, such denial can go on for years and make the challenge doubly challenging: not only do people deal with a challenge that doesn’t go away, but by insisting on a miracle to resolve the challenge, they rob themselves of the peace that acceptance of their situation could bring.

To sum up, this book dispassionately presents a variety of perspectives on miracles as they are actually held by real people. Rather than merely give these perspectives abstract names (e.g., “skeptical debunker” or “faith healer”), we also provide names and faces. This makes our discussion personal and memorable, and also avoids shoehorning people into categories that they don’t precisely fit. Hence, The Faces of Miracles.

As already noted, this is a work of clarification rather than persuasion or proof. Our aim is to assemble a rich diversity of perspectives on miracles, presenting them on their own merits and in their own voice, letting the reader draw comparisons and form conclusions. Why is such clarification about miracles important? We live in an age that craves pat answers. Miracles happen and anyone who disbelieves in them is a knave. Miracles don’t happen and anyone who believes in them is a fool. The truth is more complicated.

Bill Dembski

Alex Thomas

————————-

References

Earman, John, Hume’s Abject Failure: The Argument Against Miracles (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

France, Anatole, The Garden of Epicurus, trans. Alfred Allinson (New York: John Lane, 1908).

Gardner, Martin, “Arthur Koestler: Neoplatonism Rides Again,” World (1 August 1972): 87–89.

Hanson, Norwood Russell, What I Do Not Believe and Other Essays, eds. S. Toulmin and H. Woolf (New York: Springer, 1971).

Lewis, C. S., Miracles: A Preliminary Study, revised edition (New York: HarperCollins, 1960).

Shakarian, Demos, The Happiest People on Earth, as told to John and Elizabeth Sherrill (Old Tappan, N.J.: Chosen Books, 1975).

Shermer, Michael, “Anomalous Events That Can Shake One’s Skepticism to the Core,” Scientific American, October 1, 2014, available online at https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/anomalous-events-that-can-shake-one-s-skepticism-to-the-core/.

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr I., The Oak and the Calf: Sketches of Literary Life in the Soviet Union, trans. H. Willetts (New York: Harper & Row, 1975).