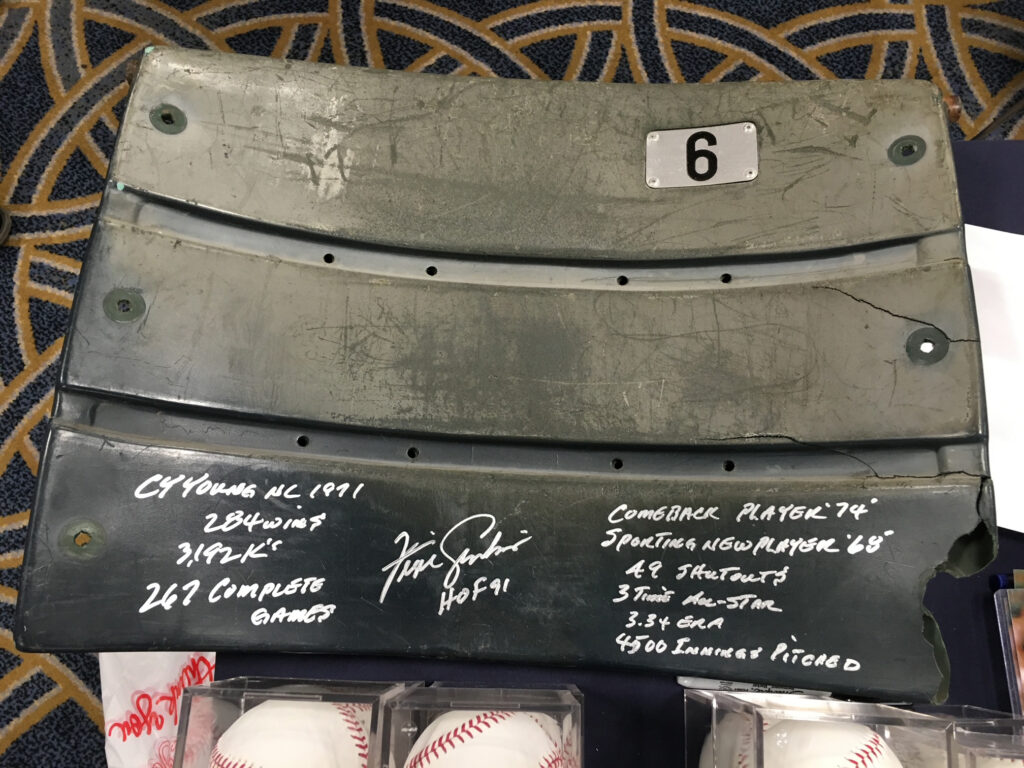

Ferguson Jenkins, or “Fergie,” is not just one of baseball’s greats, but one of baseball’s Hall of Fame’s greats. He is the last pitcher to have achieved seven twenty-or-more-win seasons. Fergie’s “dream season” came in 1971, when he had an incredible strike-out-to-walk ratio of better than seven, won twenty-four games, and was awarded the Cy Young.

Pitching in the MLB from 1965 to 1983, and mainly in the National League, he faced the likes of Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Pete Rose. Best known for his time as a Chicago Cub, he was at the 2017 Cubs Convention in Chicago in January 2017 (a few months after the Cubs’ historic 2016 World Series victory). That’s where my friend Curtis Baugh and I caught up with Fergie.

In the interview, Curtis and I focused on Fergie’s pitching, especially on his habits of mind and unusually effective training techniques. There’s no pitcher like Fergie these days. He routinely pitched over 300 innings a season (these days pitchers are lucky to throw 200 innings in a season), threw batting practice for fun, and was amazingly durable. Given all the arm injuries and surgeries facing pitchers these days, this interview with Fergie offers many lessons for contemporary baseball.

If you love baseball and have any sense for the history of the game, you’ll want to carefully study this interview. But Fergie is not just a great pitcher; he is a great man. For a window into Fergie’s life, how he has handled remarkable success as well as terrible tragedy, see the follow-up interview with Fergie by my colleague Rich Tatum, right after this interview (scroll down).

We want to thank Fergie Jenkins as well as Carl Kovacs, President of the Fergie Jenkins Foundation, for making these interviews possible. It was a busy time at the Cubs Convention. Fergie, Carl, and the Foundation could not have been kinder in sharing with us Fergie’s wisdom about pitching and life. Thanks and we love you all!

Because this interview was an unscripted dialogue, the transcript below has been lightly edited for readability, yet it preserves the original sense throughout.

Introduction

Bill Dembski: It’s an incredible privilege to be with you here today. I’m a Chicago kid, so I have lots of memories of the Cubs growing up. But I have one memory of an eleven-year-old friend of mine saying, “I’m going home to watch Fergie Jenkins pitch.” Now, normally we’d say, “Watch the Cubs.” That’s the only time I recall a friend saying, “I’m going to watch this Cub.” You were a phenomenon back then.

I was in Chicago during the (infamous) 1969 season. You had six twenty-plus games winning seasons (twenty-games or more) in Chicago, and then you had still another one with the Texas Rangers. It’s unprecedented what you accomplished, and your durability as a pitcher is just amazing. You were putting in 300-plus innings a season, and now pitchers are lucky to go over 200.

You’ve got a lot of lessons for us. What I’d really like to do in this interview is focus on the season when you got the Cy Young, 1971. That provides a window into your career. I’d like to use that season as a pivot point for asking you questions about pitching, and drawing lessons for our present age. The Cubs have just won the World Series, and that’s all great. But I don’t want to focus so much on that. I want to get your wisdom, especially for a new generation, reviewing what you accomplished on the field and what lessons can be learned.

The Pitcher’s Arm

Bill Dembski: One of the things that really motivated me to want to do this interview with you was a book by Jeff Passan that appeared last year, The Arm: Inside the Billion-Dollar Mystery of the Most Valuable Commodity in Sports. The arm here is the baseball pitcher’s arm. This book talks about how kids are burning themselves out: they’re doing too much or too little or whatever. I’ve got a teenage son. We were living in Texas. He is a pitcher. Three of the kids that he pitched with in Texas have now had surgery on their arms. These surgeries have just gone through the roof—so many kids are now going under the knife. So I’d really like to get your wisdom on how to help prevent that.

That season when you got the Cy Young, you had twenty-four wins and thirteen losses. Where my eyes bugged-out was your 7.11 strikeouts-to-walks ratio. You were in the zone that season. Can you tell us a little bit about that? Because that’s just wild—pitchers often get two-to-one ratios. You never matched that performance again.

Tell us a little bit about that season and what was going on, why things clicked that much for you.

Fergie Jenkins: Well, I’d already won twenty games I think four or five times. I went to Spring training with the attitude that for our ball club to rebound from ‘69, someone had to have a good season. At the time, we had Kenny Holtzman, Bill Hands, myself, Rich Nye, and Joe Niekro. And we were the starters—we were all young. So I just told myself that if I was going to have a good season, I had to be consistent. And consistency I think in the long run gave me the opportunity to win ball games. I knew over the course of the season I’d have thirty-five-plus starts, maybe even forty—which that year, I think I had thirty-nine, and I had thirty complete games. I ran all time.

To be consistent, mentally, you have to be prepared to pitch, and I was pitching every third or fourth day. The odd time Leo [Durocher] would push me ahead on a consistent basis, we’d had a series where we played like four games, and I did it twice. I tell people this all the time. I pitched Monday, Thursday, and Sunday. I don’t know how I did, but I was able to perform in that direction, and my direction was to be positive every time I went out there.

And I enjoyed pitching. I think that’s what you have to have nowadays. If you’re going to be a pitcher on a staff: you have to enjoy going out there. Doesn’t matter what team you’re facing. In the National League, Pittsburgh was a strong ball club that hit well against me. Sometimes the Phillies, the Dodgers, and San Francisco.

So you had to tell yourself that you had a game plan before the game, and you had to have a game plan before the game was over. Early in the count with certain hitters, you had to know how to get them out. Early in the ball games I might give up runs, but it didn’t do me a benefit to give up runs late because our bullpen wasn’t that strong. So I had to tell myself from the seventh through the ninth that I had to keep throwing strikes, make the hitter do part of the work, and stay ahead of him in the pitcher’s count—especially my count, and to get him out.

So in that respect, I think that gave me an opportunity to win a lot of ball games. And in that ‘71 season, if you look at the stats, that year I won twenty games, I had twenty complete ball games, I had over twenty hits, and I had over twenty RBIs. I had six home runs that year. I helped myself a lot of times winning ball games. But that’s something that a lot of pitchers really don’t focus in on. When you go to the plate, don’t be an easy out. Try to help your ball club in a lot of respects. Oh sure, you can sacrifice yourself by bunting, moving the runners up, but it’s the opportunity for you to get a key hit. I always said to myself, “Don’t give yourself up as a player when you go to the plate. Try to be a hitter yourself.”

Conditioning and “Doorway Exercises”

Bill Dembski: It’s phenomenal that you got six home runs that season.

You say you love pitching. When I look at your numbers, you’re pitching over 300 innings a season. That’s a lot. That’s like a work horse! And I consider also what you were getting paid back then—in that regard, I want to talk to you about the Harlem Globetrotters because you had to be doing two jobs. If you were pitching nowadays, getting the sort of stats you were getting back then, you’d be getting 20 million or so a year. But I looked at what you were getting. It was about $100,000 plus or minus. With the Consumer Price Index, which gauges inflation, you were at $500,000 to $600,000 by contemporary standards. So I love hearing you say, “I loved pitching.” It’s like you didn’t feel put upon. You wanted to be out there. But you were also durable. All that pitching didn’t seem to bother you.

I’ve read your four autobiographies, one when you had that great season in 1971, and then when you got in the Hall of Fame, then when you were doing the Canadian Baseball League, and then the most recent one from 2009. You love the game, you love pitching. But there was a durability that you had, and I want to focus on that a bit. You said a moment ago that you just ran all the time. That isn’t so much running from one ball park to another, that’s conditioning…

Fergie Jenkins: Definitely. I ran track in high school. So I wasn’t afraid to run. And Joe Becker was a pitching coach that made us run line to line, foul line to foul line, so we had to run across the outfield.

Bill Dembski: That’s 300 feet?

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, keeping your lower-half strong from your waist down, that meant strong legs. And then I had an attitude about getting certain hitters out. And Randy Hundley and I, before a ball game, would go over the hitters—the first eight or nine guys in the lineup—and then the other two guys that might be pinch-hitters, or the guys that might be on base after somebody got a base hit, where you had a substitute player come in to base run. I had to know how to hold those runners on. I tried to keep myself mentally strong.

And in that book [Inside Pitching, written by Fergie in 1971], I did a lot of what they call “doorway exercises” [these are isometric exercises where you’re pushing with your arms in various directions against a door frame]. They were something that I always did as a youngster. I just think that making your arm strong was something that I enjoyed doing. And you don’t see it nowadays, but I threw batting practice in-between starts. I used to throw to the extra men, a good eight to ten minutes. If we had four or five extra guys, they’d get maybe six or seven swings apiece. And throwing batting practice gave me that consistency to be around the plate a lot.

Bill Dembski: When you were doing batting practice, what were you taking off your pitches from what you were doing in a game?

Fergie Jenkins: I’m trying to throw as many strikes as possible, to see exactly the movement of a lot of my pitches. I might intervene and maybe throw the odd change-up, the odd slider, but control was something I worked at.

Bill Dembski: But you weren’t…

Fergie Jenkins: No I wasn’t throwing hundred or ninety percent, I might throw sixty-five or seventy percent, but I was around the plate throwing strikes.

Running & Weight-Training

Bill Dembski: I want to read from this wonderful book on pitching that you did—I would love to reprint it! Inside Pitching starts so elementary, but there’s so much wisdom in it. You write, “Running is the most important exercise a pitcher can do. Remember your legs as well as your pitching arm must be in superb shape.”

As I read that, I wondered how much that’s emphasized these days. When you think of pitching, you immediately think it’s about the arm. And the core is also big these days.

Fergie Jenkins: Definitely.

Bill Dembski: But running doesn’t seem to get emphasized. How much running were you actually doing?

Fergie Jenkins: We started in spring training, as I said, running line to line. We used to do it the entire season.

Bill Dembski: How many times would you run?

Fergie Jenkins: We ran twenty sprints a day, the relievers ran ten. In the course of having batting practice on the field, we would run when the batting practice was almost done. At the home ball park, we would run. And we’d run early, sometimes, on the road. But that was something that was a consistent exercise, we did it all the time. Nowadays, the players have weight rooms, which is not bad for certain guys. The Cubs have a weight room that’s a combination Gold’s Gym and L.A. Fitness. You think about any exercise machine that you can have, and they use them. But you don’t see the guys run as much. And I think that running, to me, as an individual, made me stronger when I was out there pitching.

Bill Dembski: Interesting. So if you were to redo it, would you get rid of the Gold’s Gym there?

Fergie Jenkins: No. You know, in the era when I was pitching, if you wanted to work out, you had to go to an exercise area, a health club. Now the health club is right there in the stadium. So you do what you want to do to make yourself strong. I would probably get on the weights if that was there for me, maybe to strengthen my shoulders.

I never lifted weights as a kid. I used to swim a lot, and I ran track as I said. But I just did things that were good for me. I had a weighted ball I used from time-to-time, but other than that I never lifted big, heavy weights.

Bill Dembski: That’s the interesting thing: as I’m looking at what the so-called best trainers are doing to get young kids into the minors and then MLB, it’s huge dead lifts, it’s big body movements, big weights. I’m sure there’s a place for that, and yet it hasn’t stopped these kids from blowing out their arms.

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, I know the elbows are a big thing now, with the Tommy John surgery. If you blow your shoulder out, your career is done. Now they can repair your elbow and maybe your wrist, but they haven’t come up with a good shoulder operation that would give them the opportunity. Because everything is rotated though your shoulder. The power is done through the upper part of your body, all the snapping part of it is done with your wrist. I threw a slider—which was considered a cutter back then. I didn’t snap the ball; I cut it, and there was no pressure on my elbow. I never had any surgeries. So, knock on wood. As I look back, it could’ve been genetics, it could have been the form I had throwing, my wind-up. I was long and lean. As I said, I didn’t lift weights.

Bill Dembski: You also say that to pitch well you were chopping wood with an ax, and you had a small sledgehammer that weighed five pounds.

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, that built my shoulder up, because I was a skinny kid growing up. When I signed, I weighed 180 pounds, but in high school, when I first played ball, I weighed 145 pounds. I was just a lean kid, and to build my shoulders up, I would chop wood in the off-season.

Bill Dembski: How long did you continue chopping wood?

Fergie Jenkins: I did it for something like ten years. And then one afternoon, I stopped. But it was something I did every winter. We had a small fireplace in our farm house, so would chop wood, and it was something so that when I came home in the off season, my dad said, “Okay, let’s go; we’re going to go gather some wood,” and I’d chop kindling for the fireplace. But other than that, the sledgehammer was unique.

Bill Dembski: Did you use two hands or one hand on the sledgehammer?

Fergie Jenkins: No, I had a five-pound sledgehammer, and would use one hand to pound it into a pillow to work on my breaking ball.

Curtis Baugh: So more to build strength than…

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, especially for my forearm.

Bill Dembski: Was it a full sledgehammer or…?

Fergie Jenkins: No it was a small, five-pound sledgehammer.

Bill Dembski: Five pounds, that’s it.

Fergie Jenkins: Or a ball-peen hammer.

Bill Dembski: So that’s it, that’s what you were doing for conditioning? How long would you pound the hammer at a given time?

Fergie Jenkins: I might do it fifteen, twenty minutes every day.

Bill Dembski: That’s a lot!

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, that is. It’s to build the strength, make your arm tired. And then I would stop.

Bill Dembski: But this is significant, because when I look at what is state-of-the-art weight training, it’s real heavy weights. I know of a very famous power hitter who just recently retired because of a neck injury; I saw him dead-lifting over 500 pounds. But in that case, you’re only doing maybe four reps, five reps with those sorts of weights.

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, consistency is key—you keep doing the reps until your arm burns a little bit, and then you stop. As I said, I wasn’t lifting heavy weights. But I’d do the exercise to the point where I got the strength out of it. And I also had the weighted ball. I would do that exercise a lot of times between starts for my wrist, because I threw a lot of pitches that were hand pitches. With my change-up, I used to spread my fingers. And with my slider it was all about finger-grips, pulling the ball.

Bill Dembski: Interesting. So with the weighted ball, were you throwing the weighted ball or were you just…?

Fergie Jenkins: No, it was an eight-pound girls’ shot put, and I would tape it for grip. I would just hold it. Mariano Rivera had one for a while when he was in the bullpen, I’ve seen him exercise with it.

Bill Dembski: You make a very important distinction in your book Inside Pitching: there’s the healthy arm, there’s the tired arm, then there’s the sore arm. It seems you virtually never got to the sore arm stage. Tired arm, you say, “That’s okay,” but then you’ve got to watch it because you don’t want it to become a sore arm.

Fergie Jenkins: Well, with the exercises I did in-between starts—I think those exercises really helped me.

More than anything else, I didn’t become a pitcher until I was fifteen or sixteen years old. I didn’t pitch in Little League; I was a first baseman. The adage is, put the tall, skinny kid on first base. I had a decent glove, and I could stretch. I didn’t start to pitch until one of our pitchers—a young man by the name of Jack Howe—came up with a sore arm. I volunteered to pitch, at age fifteen. And I didn’t think ever, three years later, I would sign a pro contract.

Curtis Baugh: So that was the beginning?

Fergie Jenkins: Yes.

Pitching Greats

Bill Dembski: From ‘65 to ‘83, during your career in the MLB, was an incredible time to be pitching. When you were still pitching, you were with Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Willie Mays. So you were with all these greats.

Fergie Jenkins: There were so many good hitters back then in the National League, from Dick Allen, like you mentioned, Tim McCarver, there were so many good ones—the lineup that most ball clubs had then were seven or eight good hitters. And they didn’t swing at bad pitches. They were pretty consistent from top to bottom. Especially when you looked at the Dodgers: Maury Wills, Junior Gilliam, the Parkers, the Davis brothers, [Ron] Fairly. These guys were switch-hitters, a lot of them, and they didn’t swing at bad pitches, so you had to make them put the ball in play or, if you had an opportunity, you might be able to strike them out.

Clemente with Pittsburgh and Stargell, Sanguillen, Roberts, Al Oliver. There were so many good players on some of these ball clubs. They weren’t patsies, they didn’t lay down for you. And the Giants, like you said, they had Mays, McCovey, Jim Ray Hart, Davenport, Haller—there were so many guys in their lineups a lot of times, and they had the Alou brothers that were there with the Giants for a while.

They didn’t lay down for you, they weren’t giving up easy, so you had to get them out.

Curtis Baugh: Did you have special pitches for any individuals?

Fergie Jenkins: Well, I studied certain guys. I had a pretty good slider.

I played winter ball two years in Puerto Rico, and I had a chance to see a lot of the good Latin players like Perez. Clemente was there, and so were Cepeda and Gonzalez—there were certain guys that you had a chance to see at eighteen, nineteen, twenty years old. So now when you got to the big leagues, I’d notice these guys, I’d see their tendencies.

But I used to always pitch to my strength, which definitely helped me.

Bill Dembski: Could I ask you a little bit more about the legs again? In preparing for this interview, I was looking at some of the stats. Ernie Banks was a household name when I was growing up in Chicago, and you had so many nice things to say about him in your books. You look at Ernie’s stats in the ‘50s and they’re every bit as good as Hank Aaron’s.

You get to the ‘60s, and it’s a different story. One of the things you said in your book, and this is what got me thinking about the importance of legs in baseball, is that Leo Durocher would always be getting on Ernie for not taking a long lead-off, because he just didn’t steal bases. So I looked at Ernie’s stats in the ‘60s: his stolen bases stat was absolutely minimal. But you look at Hank Aaron, and his stats for stolen bases actually went way up in the ‘60s, way beyond where he had been in the ‘50s.

Fergie Jenkins: A lot of times, for a power hitter, you wouldn’t think he would try to steal. If he hit a single, he’d lull you to sleep by just standing there—then, boom, steal! He might steal twenty-for-twenty; nobody threw him out. He never really stole third, but he’d get into scoring position by getting to second. Cepeda was like that from time to time, and Mays. There were some larger players—I’m trying to think of the third baseman, Shannon—Shannon with the Cardinals. You knew Brock was going to steal, maybe Flood, but not Shannon. So don’t go to sleep not holding him on, don’t let him get that extra foot-lead—boom, gone!

Bill Dembski: With Hank Aaron, did he work on his speed in the ‘60s in a way Ernie didn’t? I’m just wondering if that may have been the difference-maker, because you said that…

Fergie Jenkins: No, maybe Ernie didn’t have that speed-of-foot where Hank Aaron did. Hank was a decent base stealer and he played pretty good outfield, because he never played any other position, the outfield. Ernie was in the infield—he left from short and went to first. So they put the slower-foot individual—a lot of times, a guy with the good glove—they put him at first base. So Ernie’s job was to drive runs in. And, as I said, Leo would get on him, and shout, “Get up, get up, get another step!” And Ernie didn’t want to steal; he didn’t want to get thrown out at first on a good pickoff play.

Ernie had his job given away four different times: Dick Nen first, John Boccabella, Lee Smith, and Willy Smith—and one other player, I can’t think of his name right now—and Ernie’d win it back every year, because Ernie would just be patient. One of those guys would go oh-for-four, Ernie would pinch-hit, hit a double, or a home run. So Leo would put him back in the lineup. Ernie would go three-for-four. Ernie hit with his hands—a very smart hitter, a very, very smart hitter—and wouldn’t get cheated on certain pitches. And he was a line drive hitter, put the ball in play.

Being Discovered

Bill Dembski: Tell us about Gene Dziadura and the crucial role he played in bringing you into professional baseball.

Fergie Jenkins: Gene Dziadura—he was born in Windsor, Ontario; played with the Cubs, hurt his back; came back to the University of Windsor; went to graduate school, got his teaching degree; and started teaching at one of the local high schools, the collegiate high school. I went to the boys’ tech school, CVS, and he would come over and just watch me play a little hockey, basketball, that type of thing. And one afternoon, he just said, “Hey, everybody knows that you want to be a professional athlete. Your quickest way—because I’ve seen you throw—might be through your arm, as a pitcher.”

And we started throwing in a local gymnasium.

Bill Dembski: So you were working out with Gene, and then Tony Lucadello came down and watched you.

Fergie Jenkins: Tony was the head scout. He came down and watched me throw some ball games. He was a very small man, about five-eight. He wore sunglasses all the time. And he wrote that book, Diamonds in the Rough. He’d watch players, and well before I became a Major League ball player, he could see their potential.

Bill Dembski: What is it about being able to see potential? Is it a gift? What allowed him to see it? Because I’ve read he didn’t even want to use speed guns or anything like that. He just had a knack for spotting talent. Today, you’re supposed to read Moneyball, you’re supposed to look at the stats, and that’s how you are supposed to determine value. But Tony saw something in you—and not just you, there were a whole slew of.…

Fergie Jenkins: Grant Jackson, Alex Johnson, Billy Sorrell, so many guys, Larry Cutright as a catcher. I just think that he watched so many youngsters work the sandlot and play. I was hungry. I wanted to be a professional athlete really bad. The number one thing that drove me, the only game you could see was “NBC Game of the Week” on Saturdays, and then the Minor Leagues. You know the Yankees always played Washington, the Yankees played the Detroit Tigers, or San Francisco always played the Dodgers. I said, “One day, I’m going to be facing these guys.” And I kept saying to myself, “It’ll eventually happen.”

I worked at it. I leap-frogged the “bonus babies”—I had a very small bonus, $6,000 to sign. Some of these guys got a $100,000, $85,000 $90,000 right out of high school and college. I said, “I could play with these guys.” I knew I could play with them. I just needed that opportunity.

The Mental Game

Bill Dembski: We’ve focused a lot on your achievements and also conditioning. I’d like to shift gears a little bit to the mental game of baseball because that’s such a big deal also. I’ve been pivoting off that 1971 season when you got the Cy Young and your stats were through the roof. But let’s focus on some specifics of that season:

Game one, you did the season-opener at St. Louis: ten innings, you allowed one run; and Bob Gibson allowed two runs, so you beat him. That’s a great beginning, two to one, so your ERA, because it was ten innings, was actually less than one, since you only allowed one run. So you do that, that’s a great way to start and you’re on a roll. But I want to move forward to game forty-five. I don’t know if you remember that. That was St. Louis beating the Cubs ten-to-nothing, and you were the pitcher. Up until then you had real strong outings, but in that game you allowed around seven runs. Next outing for you, it’s against Pittsburgh. Cubs lose in a six–oh shutout, and you also allowed a few runs. Next outing for you after that, it’s the Atlanta Braves. You beat them eleven-to-nothing, and you personally get the shutout.

What happens with a pitcher when games get away from him? Even if you make the right pitch, things can get away from you—for any pitch that’s thrown, there’s a way to hit it and get something out of it. So how do you get your mind back in the game when things go wrong, and get it right again?

Obviously, things are not always going to go the way you want it.

Fergie Jenkins: Well, my terminology for it is “Getting beat up.”

So if the manager leaves you out there for X amount of runs, you’re getting beat up. A lot of times Durocher wouldn’t let that happen. You go three, four, five runs, he got you out of there. The embarrassing part of it, when you lose a ball game like that, is saying to yourself, “I got three days before I get back out there again, and I’m not going to have that bad a performance.”

So a lot of it is mental, and then you’ve got to make it a physical situation where you’re going out there with the intention of not giving up those runs, staying ahead of the hitter, and possibly winning the ball game. Your teammates are thinking the same thing.

When you go out there and you’re a consistent player, they can see that. Players that play behind you, they know when you’re out there, when you don’t have your good stuff. Or maybe you have great stuff, and they can feel that. The performance you get with them constitutes you pitching a good ball game a lot of times.

Bill Dembski: Some players, it seems, feed off of aggression. I never got that sense from you. It seems like you wanted to assert yourself. There was a duel of sorts between you and the batter on the mound. But it wasn’t that you were angry or had a chip on your shoulder. I don’t want to put words in your mouth—maybe you did—but I never got that sense. What was the attitude…?

Fergie Jenkins: No, I might have to face a Seaver, or a Gibson, or a Drysdale, or Carlton, or whoever–I knew that if I could give up very few runs, I had a chance to win. But if I gave up X amount of runs, I knew I was going to lose, because they’re doing the same thing I’m doing: they’re pitching to be consistent, they’re pitching to have less runs against them. The defense enters into the picture, and then the offense.

You’ve got to wait sometimes for your offense. I think in ‘68 I got shut out five times one-to-nothing. Nothing I can do about that! I do the best I can do to try to hold the other team to very few runs. But then you lose one-to-nothing; I gave up that one run. I also faced guys on a streak. I faced Drysdale on a streak when he had the fifty-two games. I got Seaver in a streak when he had thirty-five. I think I had Gibson when he had a streak of around thirty. So it happens!

They’re going out there to win ball games. Unfortunately, there’s a winner, there’s a loser.

Bill Dembski: When you’re throwing a pitch—and you were so accurate—most of the time you’re happy with where it went. But then there were the mistakes, and you hope that the batter doesn’t capitalize on it—such as throwing it right over the center of the plate. But you were doing complete games—people are still doing complete games, but it’s not nearly the way it used to be. You’ve got your setup men and your closers these days, but back then you were doing complete games.

So here you are throwing well over a hundred pitches in a game. How many of those pitches are you saying to yourself, “Gee, I wish I hadn’t thrown it like that—glad I got lucky and the hitter didn’t hit it”? How much accuracy can you expect of yourself—because we’re all human? And even at the top of your game…?

Fergie Jenkins: Well, in my era, when I broke in with the Phillies, there were only nine pitchers on the staff. So you had four starters, five in the bullpen. And now, it’s kind of even, it’s twelve and sometimes thirteen pitchers on a staff, so the manager can pick-and-choose who he wants to get out there. There’s now a specialty guy, one or two left-handed pitchers that get out left-handed hitters.

So now the theory with the game is that once the starting pitcher throws 95–100 pitches, his day is over. In my era, if Leo left me in a ball game in the seventh inning, I might get a chance to hit and move the runner up, pitch the eighth, and then pitch the ninth, and so pitch a complete ball game. The theory that was followed in the ‘60s and ‘70s is thrown out the window now in the year 2000-plus.

These days I don’t know if they’d have let me stay in ball games. I might have to plead to the manager, “Hey, I’m still in control of the ball game, why are you taking me out?” I might have to plead my case not on the field but maybe in the dressing room after the game’s over. But I’d probably already be out of the game after 110 and so many pitches. I’ve had games where I’ve thrown 150–160 pitches to win a ball game and to complete a ball game. Those situations are nowadays thrown out the window.

You don’t see anybody throw 130 pitches to win a ball game. Maybe if you pitch on a no-hitter, or a shut-out. Otherwise, you’re out of the ball game after 100 pitches.

Bill Dembski: Even if a pitcher is pitching a shut-out, he may be pulled before finishing the game these days. And you have close to fifty shut-outs—just an incredible statistic! In the last game of the 2016 World Series, there was a move to take out the Cubs starting pitcher…

Fergie Jenkins: Hendricks. He threw four and two-thirds, the game’s five to one, and they take him out of the ball game. I would have pleaded to stay. Personally, I’ve never won a World Series ball game. But that was this young man’s opportunity to win his first World Series ball game. Who knows when he’s going to get that opportunity to go back again? But he was taken out of the game. I mean, it could be mind-blowing: he didn’t complain, you didn’t see any reaction. He just walked off the mound and that was it. He didn’t throw his glove.

Some guys might take it personally: “What is going on here?” They took out the other young pitcher too, who was the Cy Young winner last year. Arrieta. He’s winning the ball game at seven-to-two. They took him out of the ball game. If he’s in control of the ball game, why do you take him out? Why do you go to the bullpen?

Curtis Baugh: It’s a different generation.

Fergie Jenkins: Totally, and that’s the way the game’s played now.

The manager has the opportunity to do so many different things, some good, and some maybe he didn’t think out quick enough. He could think, “Hey, this young man is still in control of the ball game.” Unfortunately, once you pull him, you’re sitting on the bench by him now. And the bullpen’s out there.

I always thought, and this is only me, that the bullpen doesn’t feel the pressure of coming into a ball game when the situation is two-to-one, three-to-two, one-to-nothing. Because the reliever has been sitting out there for five or six innings watching the ball game, now the pressure is on him simply to hold that lead. Mariano Rivera—unlike Lee Smith—only pitched the ninth inning. Lee Smith would come in the sixth and pitch three shut-out innings sometimes. I’ve seen Rollie Fingers come in and throw four shut-out innings. Or Gossage, or Bruce Sutter.

Bill Dembski: They used to call these pitchers relievers. Now you’re a closer, or you’re a setup man. You’re this, that, you know.…

Fergie Jenkins: Trevor Hoffman, who’s going to go in the Hall of Fame with six hundred saves, how many times did he only pitch one inning? Mariano, how many times did he only pitch one inning? And that’s just closing the game off. You come in with nobody on, the ninth inning. It’s good for him, there’s no pressure. I don’t think there’s any pressure to that. But you come in a situation where the bases are loaded with one out, that’s pressure right there! You can’t afford to make a mistake. The pitcher who started the ball game now has given up earned runs. Now you might not give up earned runs, but either way they’re not on you.

But I think that’s where the pressure’s at, to come in and pitch a number of innings with runners in scoring position. You’ve got to do your job.

Confidence & Self-Control

Bill Dembski: You mention, in Inside Pitching, two virtues of a pitcher: confidence and self-control. There’s a duel between pitcher and batter. You mention, for instance, some of the San Francisco batters that were really up to speed.

Fergie Jenkins: Well, McCovey owned me one spring training, and I had to change my attitude towards him. I knew pitches that could get him out. But don’t make the mistake of getting the ball over the plate. You had to keep the ball hard-in on him. Clemente, the same way, hard-in. Mays, down-and-away. Let him know you’re out there and then go down-and-away. Tony Perez, Johnny Bench… So in theory I kept a book for the longest time, and then mentally I just knew how to pitch guys.

But you need to be consistent in approaching batters—you cannot stop thinking when you’re out there, inning-to-inning, pitch-to-pitch. When you stop thinking, you’re going to give up runs. So you can’t stop thinking when you’re out there.

And same with the catcher. He’s got to know when he puts that sign down whether I’ve got confidence enough to throw that pitch. If not, I shake him off—and I might come back to the same pitch. Randy Hundley and I had a game we used to play all the time, of shaking off, shaking off, and coming right back to the same pitch.

And very seldom did I shake my head. I always shook my glove.

Racism

Bill Dembski: You were starting your career when the Civil Rights Movement was taking off. In describing your time growing up in Canada, you say you really weren’t dealing with racism. But then you say you faced racism head-on during spring training with the minors in Florida, and then especially in Arkansas. You mentioned fellow player Richie Allen, who really had a hard time with the racism he encountered in Arkansas.

How did you deal with that time? Because that’s … mental stuff. You’ve got so-called fans, you’ve got local people who are giving you a hard time. How do you keep it together mentally? It seems you handled it better than some: you didn’t get bitter in the way Richie Allen did.

Fergie Jenkins: Well, I faced it first in Florida, and then when I was in Chattanooga. We had to play in Birmingham; Macon, Georgia; Knoxville, Tennessee—where the fans were behind chain-link fences and you could see them. And they would scream at you from time-to-time. If I’m in the outfield shagging fly balls and they’re screaming, just walk into the infield. They’re not going to come on the field, because if they come on the field, bad things are going to happen to them. It could’ve been a kid, seventeen or eighteen years old, screaming some obnoxious thing at you. So you just walk into the infield.

The nice thing that happened to me—and I’ve told it in my book—when I went to Arkansas, we had four players of color: Richie Allen—who changed his name to Dick—from the United States; Marcelino Lopez, a player of color from Cuba; Richie Quiroz, a Panamanian, and myself, from Canada. And we were able to survive there because we didn’t let it bother us. Three pitchers: Marcelino, Ricardo Quiroz, Fergie Jenkins, pitching. Dick Allen had to play every day.

This is the reason why he had to face more abuse than our individual talent as pitchers: he played every day.

Here’s the funny thing about what happened to him: the first game he played, he made two errors. He misjudged a fly ball to center and a ground ball. And fans got on him. They didn’t want us here and now Dick didn’t play well! And then he bought a car and they piled signs on it.

But we started to win that year, and it all went away. Dick Allen was second MVP of the league. He had so many home runs, doubles, stolen bases, and he proved that his ability there was going to get him to the big leagues, which happened in ‘63. I went back to Chattanooga for about two months and then I came back again at the end of the season. Quiroz and Marcelino stayed, and they pitched.

I just think that taking a little abuse makes you a better player. Because you don’t want to hear it anymore, so your performance needs to get better!

And that’s what happened to me. I didn’t pitch all that well, so they sent me back to Chattanooga. And then, before the season was over, I went back to Arkansas. I opened up the season again in ‘64 and ‘65, and then in ‘65 I went to the big leagues. So I just told myself, “If I’m a little better athlete, I wouldn’t stay here. I’m not going to stay in this division.” Which is what happened—I went to the big leagues. All of us went up. Richie Quiroz ended up quitting, Marcelino went up, so did Dick, and so did I.

The Harlem Globetrotters

Bill Dembski: Salaries in professional sports have just exploded in our day. But back in your day, to make ends meet, you were playing in winter leagues, Puerto Rico, and elsewhere, and then you were playing for the Harlem Globetrotters. The thing that was jaw-dropping when I read about your experience with the Harlem Globetrotters is that you were dunking the ball for them! Here you are a baseball player. You’re not playing a lot of basketball. You’re six-five…but still!

Fergie Jenkins: I went to an all-boys tech school, and I played for a team called The Cagers, so my basketball ability wasn’t bad. In 1967, Joe Anzivino was the marketing guru for the Globetrotters—they had an office on Michigan Avenue in Chicago. By September, I’d already won twenty games. I see this gentleman walking through the stands while we’re all taking batting practice. It’s September, late September. We get very small crowds in September. So this man’s walking through and he’s motioning to me in the outfield—I don’t know who he’s waving at. Rich Nye is playing left field and I’m at left center—pitchers are always shagging for the hitters. He’s waving like this, and I don’t know what he wants. He waves, and Rich Nye walks over and he says to Rich, “I want to talk to Jenkins.”

I didn’t know who he was. The guy had a three-piece suit on. I thought he was an attorney with an attaché case. Maybe I had a paternity suit or something! I didn’t know. My mind’s going crazy. I was like, “Whoa, what’s going on here?”

So he walked over, and he says, “I represent the Harlem Globetrotters. Are you going to go back to Canada when the season’s over?”

I say, “Yeah, I only play on a ten-month visa so I’m going back in October, and close up my apartment here.” We had a condo, the wife and I, and we had no kids at the time. “So I’m going to go back to Ontario.”

He said, “We’d like you to join the Globetrotters to be the pitcher in the skit each night when Meadowlark hits a home run.” I said to myself, I could do that no problem. I could palm a basketball!

But the thing was, the way he offered the situation, I said, “Okay I’ll have to get ahold of my wife.”

And he says, “I’ll give you a day to think about it.” He said, “The Globetrotters are coming to town over the weekend. Would you like to come down and meet Meadowlark or Curly?”

I knew Geese Ausbie. I didn’t know Jackie Jackson, or Mel Davis, or Leon Hillard. There were a bunch of guys on the Globetrotters that I didn’t know—but I knew a few.

Bill Dembski: This was the golden age of the Globetrotters.

Fergie Jenkins: Yes, yes.

Bill Dembski: I remember them as a kid, I mean this was…

Curtis Baugh: They were wonderful!

Fergie Jenkins: At an off day, they got ahold of me. They say “Hey, bring some shoes, shorts, shirt, and we’ll have a shoot-around.”

“Okay, no problem!”

Things like that didn’t unnerve me. So we went to a local gymnasium and had a shoot-around: different shots, jump shots, things like that, and we ran lines, things like that. And I dunked the ball a few times. I proved to them I could handle myself on the basketball court.

So, now the season’s over.

Bill Dembski: Okay, stop one moment— how were your legs in such good shape that you could have that vertical leap to dunk the ball?

Fergie Jenkins: I was twenty-two or twenty-three years old—I was dunking in high school. As a kid, fifteen-sixteen years old.

Bill Dembski: But you’re playing baseball, so you’re not doing a whole lot of basketball anymore, right?

Fergie Jenkins: I don’t know, I just had that ability, okay?

Bill Dembski: Okay.…

Fergie Jenkins: Now the season’s over, we open up in Shorebrook, Ontario. We go from there to Ottawa, to Montreal, the Three Rivers, and I was only supposed to play like twenty games. But what had happened got such an impact from the crowd, they decided to extend it, to continue it.

My skit with the Globetrotters always started in the third quarter: I’m sitting on the bench. Meadowlark looks around, and he says, “Come on, let’s play some baseball!” Like that.

And Curly says, “Well, we need a pitcher.”

Jackie Jackson says, “I’ll pitch!” Jackie throws one over Meadowlark’s head.

Meadowlark says, “Don’t we have a twenty-game winner on our bench? From the Chicago Cubs?”

I’m still in my sweats, and people are like, “Who the hell’s the twenty-game winner with the Cubs?”

So I take my sweats off and run back out, and they announce “It’s Fergie Jenkins with the Chicago Cubs!”

So, I pitch, give up the ball, he hits it into the seats, he’s running around, gets all the way to home plate, they throw the ball in—by that time I’ve already snuck down to the basket.

Curly says, “I got you tonight Meadowlark!”

Meadowlark says, “No—Superman!” He slides in safe.

Curly gives him the ball and he throws. If he doesn’t make the hook shot with the first throw, I get it back, throw it back to him again. If he misses the second time, I just dunk the ball. So now I get a laugh.

Oh yeah, “Fergie Jenkins, baseball player, is dunking the ball.” That’s how it started.

Bill Dembski: So either way nobody can lose.

Fergie Jenkins: I did about thirty-five, forty ball games that first year. The next two years I did sixty, I played something like 180 games in three seasons with them, in the off season.

The Cubs didn’t mind until we played here at the Chicago Amphitheater. I scored about fifteen points and the front office got back to me: “You’re playing more than we thought. You’re playing the third quarter, fifteen minutes each night!”

They didn’t dislike me playing:

But they made it clear: “Don’t get hurt.”

I wasn’t the star on the team. The stars were Meadowlark, and Curly, and Jackie and these guys. But in the course of those three season I played with them. It was fabulous. I made some decent money. But now the new season has started. I said to the wife, “It’s 1970. It’s getting to be too much. I can’t do it.”

I’m twenty-five or twenty-six years old now. And I’m still winning twenty games. And the nice thing about it is that I was in decent shape. The running on the court didn’t hurt me because, like I said, I ran all the time. But the shooting was more of a challenge. We were on buses. With every different city you visit, you’re always on a bus. When we went to the bigger cities like Pittsburgh, L.A., and San Francisco, they would fly me in and have me do radio and TV, maybe some newspaper interviews: “Twenty-game winner Ferguson Jenkins is playing with the Harlem Globetrotters.” By that time I’d already won twenty games three years on a row: ’68, ’69, and ’70.

The fun part of it, as I look back, was the camaraderie. I was playing another sport, and they welcomed me into their world. You know, they didn’t have to do that. Meadowlark, from time to time would say, “You can handle yourself, you should’ve been a basketball player.”

I said, “No, no, no, I’m a baseball pitcher. No, no.”

Jackie Jackson and I would go out to eat in certain cities. I used to know places to go like in San Francisco and Oakland, because we’re playing in these cities, so I knew some of them. And likewise Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

The Globetrotters also played in New York at Madison Square Garden. I only got nervous once playing basketball, when they introduced me the first time in Madison Square Garden. I ran out there and I said, “Man, this is big time right here.”

But I’d already run the lines, warming up. It was me being introduced that told me you’re in New York, and this is basketball country right here.

We played also at the Checkerdome in St. Louis and at the Cal Palace in San Francisco. It was fun doing it. And we played the Amphitheater here in Chicago. It was playing in another capacity. It was fun, it was fun.

Those three seasons I played for the Globetrotters were so much fun. And I made a little money too.

Almost a Second Cy Young Award…

Bill Dembski: Let’s talk about 1974. You were traded that year to the Texas Rangers because the previous year you had your first losing season with the Cubs. In 1974 you actually had a better win-loss percentage than any of your prior seasons—you were the comeback kid, twenty-five and twelve. You had a phenomenal season in 1974.

Fergie Jenkins: I beat Oakland five times that year, but still Catfish Hunter got the Cy Young.

Bill Dembski: That’s what I wanted to ask you about. That year you were Cy Young number two after Catfish Hunter—you were the runner up.

Fergie Jenkins: I say to myself, “Who watched me pitch that year?”

Bill Dembski: You mentioned in your most recent autobiography that there was a riot at a game in Cleveland where you should’ve gotten a twenty-sixth win.

Fergie Jenkins: That win, that should’ve been twenty-six.

Bill Dembski: But your team, the Rangers, won by a forfeit instead of you getting the victory because the fans got beer for ten cents that night.

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, ten-cent beer night. I would’ve won twenty-six games that year.

Bill Dembski: So, here’s the question, because it was twenty-five and twelve for both Catfish Hunter and you. If you’d gotten that twenty-sixth win, do you think you would have gotten the Cy Young?

Fergie Jenkins: Well, who knows? The umpire gave the team the win because the riot started.

But prior to the game, we’d had a fight the week before against Cleveland. Lenny Randle bunted a ball down the first base line after Milt Wilcox had thrown at him, and they got into a fight. So everybody thought that when we came into Cleveland, that we would have a little donnybrook again. And it just happened to be ten-cent beer night. It was only like eight or nine thousand people in the stadium.

Bill Dembski: A perfect storm.

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah. We had a streaker. A woman dropped her top. Guys mooned and then ran on the field. Nobody stopped them. And the umpires, they didn’t have the authority to stop people. There was no security the way they have it now in the stadiums. Somebody runs on the field now, and they get you before you get too far.

We had a father and son moon people in center field and then they ran over the center field wall. It was the old brickyard.

The Pitcher’s Mound

Bill Dembski: I’m not sure we want to end the interview on this! Let me ask you one last question, which is not going to be about mooning!

Fifteen-inch mound to twelve-inch mound, how much of a difference did that make for you? [After the 1968 season, the pitcher’s mound in Major League Baseball was lowered three inches to give an advantage to batters. Fergie was right in the middle of this change.]

Fergie Jenkins: Never bothered me.

Bill Dembski: Never bothered you.

Fergie Jenkins: Never bothered me because I worked at it. Spring training came around, and the mound was lower. The tallest mounds were in Houston and with the Dodgers at Chavez Ravine. A very low mound was in Detroit. A low mound was in Philadelphia. Chicago had a good mound. For Cincinnati, it depended on the pitching staff, really. But I didn’t let it bother me. My attitude was, even though the mound’s low, just go out there and do your job.

Bill Dembski: How much speed would you say lowering the mound took off your pitches, one or two percent?

Fergie Jenkins: It took away from the breaking pitches, not so much speed from my fastball. The game is a downward game. As a pitcher, you throw down more than anything else. It didn’t take away from my slider or my curveball or change-up.

Bill Dembski: Thank you very much. It’s been a pleasure.

Fergie Jenkins: All right.

Postscript: Bill Buckner seemed like a really sweet guy. Shortly after having the privilege to meet him at the 2017 Cubs Convention, I saw the ad below, which brought a smile to my face, especially given that I remember well how an error by him in that infamous game against the Mets lost the Red Sox the 1986 World Series. The ad poked good-natured fun at what by then was ancient history. Both in the ad and in my meeting with him, Buckner seemed alert, friendly, in good shape. I was therefore shocked to learn that he died of dementia in 2019. How quickly that must have set in.

+++++

The Life Wisdom of Fergie Jenkins

On Saturday, January 14, 2017, Rich Tatum was able to attend the 2017 Cubs Convention, the first Cubs convention ever to celebrate a world championship. There, Rich was privileged to interview one of baseball’s true legends, Chicago Cubs All-Star pitcher, Cy Young award winner, and the only Canadian in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Ferguson Jenkins.

As Rich put it about the interview, “Jenkin’s star is so bright, even this non-athlete found himself occasionally tongue-tied in the interview. While Major League pitchers are a breed apart, the gentle six-foot-five Fergie Jenkins stands out more than most.”

This interview explores just what constitutes the mind and attitude of a lifetime winner.

Rich Tatum: I’m here in lovely frigid downtown Chicago with the inimitable Ferguson Jenkins. Your friends and your fans call you Fergie.

Fergie Jenkins: Definitely, yes.

Rich Tatum: You really almost need no introduction. You’re like royalty in baseball with over 3,000 strikeouts with less than 1,000 walks, seven seasons with over twenty wins—it’s incredible, your accomplishments. You’re a Hall-of-Famer, you’ve led the league in a number of stats—but what I’m interested in is what goes into that mindset? What makes a winner?

Fergie Jenkins: I think it was from 1967 through maybe ‘82 or ‘83 I led the league in wins percentage-wise and, as you said, 3,000 strike-outs. To prepare yourself for a game, a lot of times with a four-man rotation you knew if you pitched on a Monday you were pitching again on Friday. So, you could just look at the schedule a lot of times and see what team you were going to face.I looked at their strengths. I was pitching to my strength, trying to work on their weaknesses.

And I used to keep a—they call it just a “theoretical book,” on hitters. From spring training through maybe the All-Star break until they started bringing up rookies or bringing players up that maybe might have an injury on a ball club, so they would substitute players—what I tried to do is understand if he was a right- or left-handed hitter, or a switch-hitter, what his dominant pitch was he liked to hit. If he was a first ball hitter, a hitter that hit deep in the count, or a good breaking-ball hitter. I would have that book and I would check off if Bill Hands is pitching or Kenny Holtzman or whoever the pitcher that pitched before me, I would watch hitting tendencies: guys that shortened up on the bat, like Rico Carty, with two strikes.

Rich Tatum: Right.

Fergie Jenkins: Pete Rose, took the first pitch every time you were out there pitching against him in Cincinnati, when he was a lead-off hitter back in the 60s.

Rich Tatum: You were looking for their signature, their style, their patterns of habit.

Fergie Jenkins: Definitely, right. That’s something that a pitcher should learn. You shouldn’t have to look in a scouting report because sometimes scouting reports are not good. Some of them are, some are not. They look at the hitter’s tendencies—I looked at their strengths. I was pitching to my strength, trying to work on their weaknesses.

Rich Tatum: Right, so you were matching strength against strength.

Fergie Jenkins: A lot of times, yes. Every hitter has a weakness. Maybe late in the count he chases breaking balls. Maybe late in the count or early in the count he chases high fast balls. So this was part of what the catcher—whoever I had. Here I had Randy Hundley, Texas I had Jim Sundberg, Boston I had Carlton Fisk, and with the Phillies I either had Dalrymple or Corrales, who—Corrales and I would play together in the minor leagues, Double-A, Triple-A, then the big leagues.

At lot of times the catchers and yourself would have an understanding of how we’re going to pitch a certain guy. When the game started if I was able to pitch through the middle innings and maybe get to the ninth, we understood that if we had to get to the top of the lineup again and we had a one- or two-run lead, now is the time to not make mistakes to put runners on. Don’t walk anybody, don’t give up the extra base hit and try to make the hitter hit the ball in the ground. I was—especially in Wrigley Field and Fenway Park and even in Texas—ballparks are small. My plaque in Cooperstown, it says “out of my nineteen years”—which I didn’t play nineteen years, I played eighteen years—I played in hitters’ ballparks, twelve of those.

Rich Tatum: I was going to talk about that.

Fergie Jenkins: The six years I played in Texas, we played in a stadium called Turnpike Stadium, right along the turnpike, a very small ballpark, it had a short porch to left field, not bad to right. But the thing is that you had to be very careful with the wind factor in Texas. The wind blew across and out to right and later on as nighttime really showed up, you had to be careful of the left field. In Wrigley Field you had to be careful all the time.

Rich Tatum: All the time, right.

Fergie Jenkins: At Fenway, same way—ball jumped to left field. They had the wall, sixty-foot wall.

Rich Tatum: You’ve been quoted as saying that when you step up to pitch against a batter you always respect the batter.

Fergie Jenkins: Oh, yeah, definitely. They got to the big leagues similar to what I did: working hard to get there, to get established. Then you looked at veterans, guys like Mays and Aaron and Tony Oliva. There were so many guys, Clemente, Cepeda, so many good hitters, Rose, that that respect—they’re not trying to hurt you but they’re trying to beat you. The beating part of it is, to me, wins and losses. And that’s the only way you can tell a pitcher with a strength, how many games he pitches in and the end result, how many wins he had over the course of a season or the course of his career.

I had pretty good winning percentage against certain ball clubs. I tried to utilize that every time I went out there. The team that traded me, the Philadelphia Phillies, I have an outstanding winning record against their organization, only because—I wasn’t mad because I got traded, I didn’t use that as a focal point to pitch better against them—I just wanted to prove to them they made a mistake.

Rich Tatum: That made them losers.

Fergie Jenkins: Definitely, and I tried to win. I tried to win every game I pitched, but that’s not going to happen.

Rich Tatum: But you did a pretty good job.

Fergie Jenkins: Tried to, yes.

Rich Tatum: When you step up on the mound and you face down your opponent, the batter as your opponent, what goes through your mind at that point? What frame of mind do you have? What’s your mentality?

Fergie Jenkins: The first time I face a hitter, regardless of if he’s a veteran or rookie, if I know who he is, I’m trying to get ahead in the count, stay ahead in the pitcher’s count, not the hitter’s count. The pitcher’s count is, it could be one ball, two strikes, it could be oh-and-two—means I’m ahead in the count. If I fall behind two-and-one or three-and-one, now I’ve got to throw a certain pitch that maybe he likes better than others because I don’t want to walk him. I always said that walks score eight or nine out of ten times. The lead-off hitter in innings scores.

Rich Tatum: It’s been said of you that you pitch from behind better than anybody many of your team mates knew. Is that what you’re talking about?

Fergie Jenkins: Right, I had to get even in the count. I didn’t like to get to three-and-two because that meant you’ve got to come in and throw a certain pitch. If I got to three-and-two, the number one thing is I wasn’t going to walk you. Don’t look for a walk, because I’m not out there walking you. I can throw slider, curve ball, fast ball, even the change-up, three-and-two and throw a strike with it. If you’re up there to get a walk—you’ve got the wrong pitcher!

Rich Tatum: So there are winners and there are losers, but a lot of contemporary, modern culture is giving everybody a trophy for playing. How do you feel about that? You probably didn’t raise your kids that way.

Fergie Jenkins: Well, I tried to get them to work hard at whatever they tried to accomplish. My first three girls, Kelly, Delores, and Kimberly, I tried to emphasize: nobody’s going to give you anything. You’ve got to work at it. They were very fortunate. I didn’t get a chance to go to college…so I gave them the opportunity. They all graduated and they all have really good jobs. Raymond, my son from my second marriage, he’s trying to get his master’s degree right now in criminology. He’s a pretty smart young man.

The thing was, I had the money because of the fact that there was a good pension plan, thanks to Marvin Miller.

Rich Tatum: Back to winning and losing, some people believe or seem to feel that when they face tragedy that they’re losing somehow and there are very few people that I’ve read of that have faced the kind of tragedies that you’ve had to survive.

Fergie Jenkins: Right.

Rich Tatum: How do you take a winner’s attitude and deal with tragedy? Because you don’t feel like you’re winning when you’re suffering that way or your family is suffering.

Fergie Jenkins: I try to stay positive most of the time. I’ve had as tragedies in my life, I lost my mother early, she was very young, to cancer. I lost a wife and a daughter to a car accident. I just think that talking to people, talking to the clergy, my second wife was Catholic so I had a chance to sit down and talk to a few people of the church. I’m a devout Baptist, I’ve always been a Baptist, my mother was a Baptist. I tell people I had to go to church sometimes three times on Sunday! I taught Sunday School, I sang in the choir, and my mother wanted to go to church in the evenings, so if I had to play sports on a Sunday I would try to convince my mother to have my grandmother or someone take her to church because of the fact that I had to play sports.

When I lost my wife and my daughter, I sat in a group session with people that had other tragedies, seeing drownings, or fires, or car accidents, things like that, and we all have a story in our life.

Rich Tatum: You can’t compare.

Fergie Jenkins: No.

Rich Tatum: Everyone’s tragedy is…

Fergie Jenkins: Totally different.

Rich Tatum: Is different and it’s their own.

Fergie Jenkins: Sitting and listening, having a discussion with other people that have had things like that in their life, I feel their pain, too. I had pain but I tried to make it positive. When it was done, you sit down and I have a quiet time after funerals. A lot of people to think if you cry, that’s a weakness. No, I’ve sat down and a lot of times cried by myself, sat down and cried with Raymond, my son, who at the time when he lost his mother was only eleven. When I lost my mother, my dad and I just sat. My dad was kind of the—

Rich Tatum: Stoic?

Fergie Jenkins: Well, he had a bit of weakness, too. My mother was only fifty-two when she died of cancer. My dad didn’t remarry. He stayed at home. When I bought my first ranch he ended up living with us. I had a very large house—I converted a basement into an apartment—and he lived with us for like ten years. The thing was that we just sat and we discussed that tragedy is part of life. We’re not all going to live on this earth for a hundred years. Things can happen—and my mother died young at fifty-two with cancer. I lost my wife in a car accident. She was only thirty-two at the time, and my daughter, she was only three. It was something that you can’t foresee.

Rich Tatum: No.

Fergie Jenkins: Nobody can foresee.

Rich Tatum: Or prepare yourself for.

Fergie Jenkins: Right, and you can’t compare yourself to other people. I always said you climb up that mountain and you hope the climb is gratifying, but when you’ve got to go down the other side of the mountain, a lot of times there’s tragedies.

Rich Tatum: You said once in an interview when somebody asked you about this, they asked whether you were being tested or punished and you said that sometimes you felt it was a bit of both. Do you still feel that way? Is there punishment in it or is it something else?

Fergie Jenkins: One time I thought maybe I was getting tested. They say the Lord, in the Bible, won’t give you more than you’re able to handle. At one time, I said, what is going on here? I don’t need to be tested anymore, especially when you have to bury loved ones.

Rich Tatum: Just because you can survive it doesn’t mean you should, right?

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, right, and to go to funerals, go to funeral homes or wakes, and you’re sitting there and people are trying to give you well wishes, things like that, and your loved one is in a casket. It’s a tragedy, sure, but how do you cope with it? There’s some quiet times that I’ve had by myself and just said, you know, I’m going to get through this. I’ve got three daughters, I talk to them all the time. I have a son, and we just got through it.

It took a little while. There were some times that Randy Hundley, who’s a really good friend of mine, and Ernie Banks, and Ron Santo—Ronnie and Ernie are gone, but Joe Pepitone, Billy Williams, we’ve talked about, how are you going to get through this? I said, hey, I’ve got plenty of friends, things have been working out and I talk a lot.

If it happens, I just talk about it.

Rich Tatum: You talk it out.

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, don’t hold it in.

Rich Tatum: So what gives you joy today?

Fergie Jenkins: You know, I do a lot of appearances. I started this charity: we thought about it 20 years ago, of putting on a golf-outing for the Red Cross. The second year we did it, we did cancer research for my mother and we did the CNIB, which is Canadian Institute for the Blind. Then I started Boys and Girls Clubs, other different situations, juvenile diabetes—Ron Santo had it, because he had diabetes. We started a meeting where we’d bring other ball players in, sign memorabilia, and donate monies to different charities.

I like to see people smile. I come to this Cubs Convention—this is like my twenty-first, and little kids come up to you, they’ve got no idea who you are, but the parents are telling them, “Hey, I saw Fergie Jenkins pitch, da, da, da.… He did this, he did that.” The kids, it goes right by them, but you sign their ball and they look at it and they go, “Wow, I can read it.”

I always said that, I had a math teacher, Robert Waddell, when we’ve have a test he would always tell his students, “If I can’t read your name, you get no marks. It’s not a puzzle, it’s just writing your name so I can read it, and things will be just fine.”

These situations here now of signing your name, memorabilia, people want it on a bat, they want it on a ball, on a shirt and you love to see them smile, and they thank you for it. That’s gratification and it’s respect.

Rich Tatum: You said you never had a chance to go to college, but I’ve been told you’re a great reader.

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, I read a lot of books.

Rich Tatum: What do you like to read?

Fergie Jenkins: Right now I probably read a lot of hunting books, of how to hunt, how to survive if I’m out someplace that I haven’t hunted before, maybe Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, wherever, Pennsylvania. I don’t get cold. I’m very lucky, I don’t get cold. I hunt with no gloves sometimes—or the fingertips cut out of the gloves. I’ve hunted in blizzards, I’ve hunted in windstorms and I’ve had to walk back to my truck.

I’ve been lost only one time. I was hunting up around James Bay and I got turned around in what they call a pine forest. The trees were really close together and we were hunting moose. It had snowed earlier so I had followed some tracks and all of a sudden the tracks crossed. I followed another track. The sun was in front of me at the beginning and all of a sudden, boom, the sun’s on the side of me. I went, Whoa, here. I said, do I follow my tracks back? I said, no. I didn’t have a compass, I just said, the sun’s on my right side, I’m going to continue to keep it on my right side and I’m going to go straight back.

I found the logging road. I was supposed to be back at this logging road at five o-clock. I didn’t show up to the logging road until like nine! I had a flashlight, and I had matches, and I had a gun with shells. I knew I wasn’t lost to the point where I’d have to make a fire and stay out overnight. I walked back. It took me an extra three and one-half hours. Finally, I got back to my truck and got back to the camp and the guys were all, “Where were you? We thought you shot a moose and you had a problem!”

I said, “No, I got turned around but I’m fine, I’m back here at camp.” I got back to the camp, it was like nine o-clock.

Rich Tatum: You played at the top of your league at hockey in high school. You played basketball with the Harlem Globetrotters and you played basketball in high school. You lettered five times in high school, hockey, track and field, basketball, and baseball and now you’re telling me about exploits as a hunter, and you’ve run for office!

Fergie Jenkins: Right, yeah, parliament, run for the liberal party.

Rich Tatum: You’ve managed a farm. You had to learn how to ride a horse. What can’t you do? What’s next for you? What are you going to learn how to do?

Fergie Jenkins: This Foundation—we’re trying to make sure it’s successful, working on it. It’s been twenty years. I don’t know how many more years I’m going to do it. As of right now I’m enjoying doing it. We go to different functions, we go to All-Star games, we do minor league teams. I get invited to men’s clubs and we talk, basically about my career. It’s like a meet-and-greet type situation. I sign autographs.

The other thing about reading books, I love to read sports books because every athlete has a different story, from Whitey Ford, to Willie Mays, to Frank Robinson, to Wade Boggs. Reading their biographies, it seems like after their fifth or sixth year of playing professional baseball, basketball, or hockey, everybody has a theory on what got them to where they’re at now. Bobby Hull, Wilt Chamberlain, and I’ve got all these books, and I’ve got a lot of them signed by the athletes and I had a chance to meet them, like maybe at banquets.

A rare situation, Vada Pinson, and Ernie Banks, and Curt Flood—all born in the southern states—had a chance to play under discrimination. I didn’t have a chance at that early in my life because I was born in Canada, but when I had to face it at eighteen-nineteen years old, I kind of looked at it a little differently because of the fact that, “Why do these people dislike me all of a sudden? All I’m trying to do is to be a professional athlete, move on in my career and get to the major leagues.” But there’s always something that you hear and you say to yourself, this individual doesn’t even know me, but that’s part of what discrimination is all about.

Rich Tatum: You speak about the story that every athlete has their story of what got them… What do you think your story is? What do you want people to know about the Fergie Jenkins story?

Fergie Jenkins: I’ve always told people I’m a hard worker. I enjoy work. My dad always told me that nobody’s going to give you anything, you have to earn it. My mother used to always say, “What you start, finish.” I tried to have that theory when I pitched a lot of times. I went out there, you’re the starting pitcher, if you can get to the ninth inning and be winning in this situation, why do they need to have the bullpen help you out? Just go out there and do your job. Your job is to be a winning pitcher. I tried to keep that theory going throughout my career.

It’s just something that, it’s worked for me. I’m not saying it’s going to work for half-a-dozen other athletes, but other athletes, they have their theory on what they try to do to be a winner. It could be a hitter, base-stealer. Maury Wills’s story: he played nine years in the minor leagues before he got to the big leagues because he was a switch-hitter and the Dodgers organization didn’t need switch-hitters at one time. Then he said to himself, if I can get on base I can steal bases. He studied the pitchers, stole a hundred bases a couple of times.

Rich Tatum: Reinvented himself.

Fergie Jenkins: Yeah, really, that’s it. As I said, everybody has a story. I think when you look at it, because of the fact that the odds weren’t against them but you worked to achieve a goal. I think everybody has a goal.

Rich Tatum: At seventy-four years of age, I can’t tell that you’re a day over fifty!

Fergie Jenkins: I think I’ve got my father’s genetics. He still looked young when he passed away and he still had all his hair. I started shaving my head when I was thirty. I started losing my hair.

Rich Tatum: You are finishing well, friend, and thank you for the time for this interview….

Fergie Jenkins: Pleasure, my pleasure!

Rich Tatum: And for your generosity. You’re a pleasure to meet and you’re a hero to many.

Fergie Jenkins: Thank you, appreciate that.