In my book The Design Inference (Cambridge University Press, 1998), I laid out a statistical method for uncovering the action of a designing intelligence. That method took the form of an inference—specifically, an inference to the best explanation. Thus the method asserted that if an event, object, or structure conforms to an independently given pattern (i.e., a specification) and if in the absence of intelligence the probability of matching that pattern is small (i.e., improbability), then a design inference is warranted. Simply put, specified improbability constitutes a method for inferring design. Moreover, things that exhibit specified improbability are best explained as the product of intelligence.

So what do you do if you want to avoid a design inference? Darwinists avoid design inferences in biology by arguing that the probabilities in question are not as small as they may seem. Darwinian evolution is supposed to describe a gradual process of transformation in which baby-step by baby-step, organismal change happens in probable ways so that at the end of the day even though the final product may seem vastly improbable, in fact it becomes eminently probable because each of the steps individually are reasonably probable and natural selection is able to coordinate all these probable steps, rendering the entire evolutionary transition in the end probable. So the story goes.

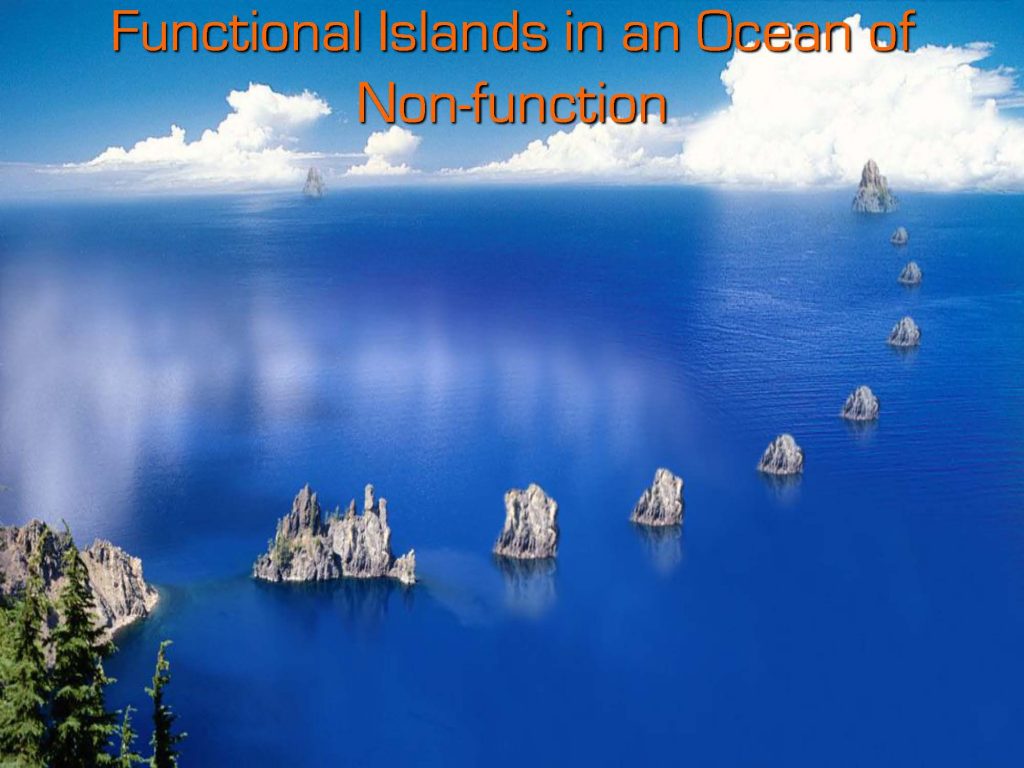

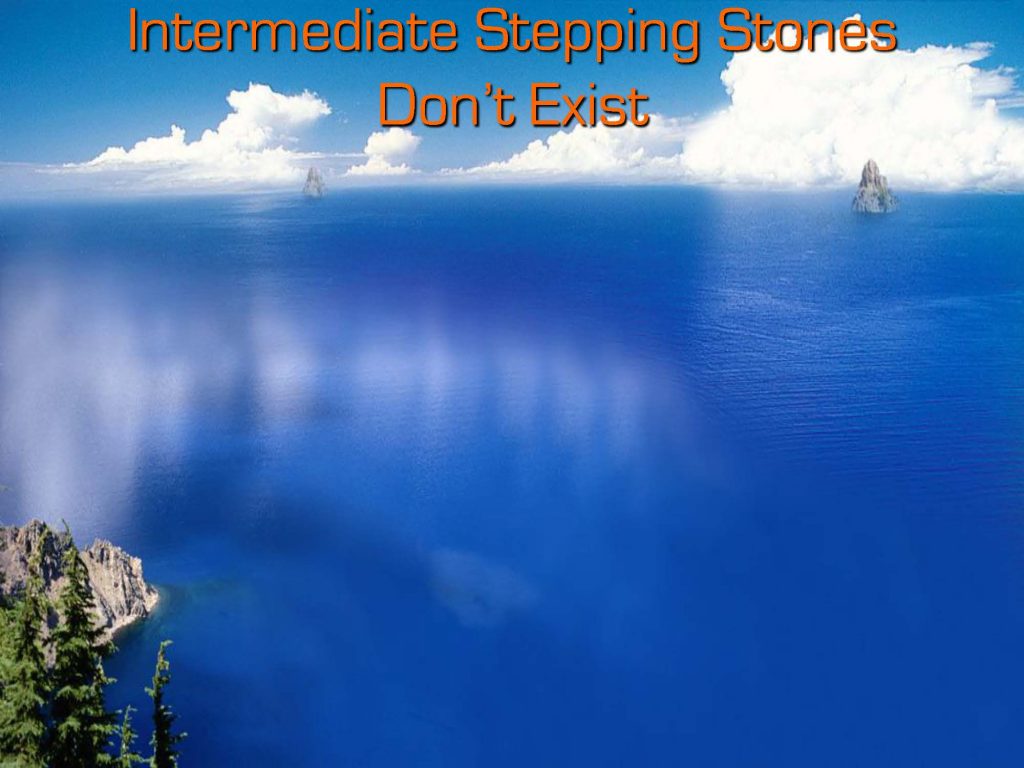

When I used to speak widely on intelligent design, I would illustrate this Darwinian approach to countering the design inference with the following two slides (from a talk I gave at the University of Oklahoma in 2007):

The first slide illustrates, by analogy, what the Darwinist thinks must be the case, namely, that islands of functionality exist dotted along the way in getting from the left most island to the farthest off island. With all these intermediate islands, it is easy (probable) to jump from one island to the next and thus get to the far-off island by starting with the closest one (the far-off island representing the end product of evolution that we’re trying to explain).

But how do we know that those intermediate islands exist? The second slide illustrates this possibility, and insofar as it describes what is happening with biological change, it renders Darwinian evolution far less plausible. It needs to be noted here that whether these transitional islands (i.e., intermediate functional biological forms) exist is a matter for fact. The dispute between design theorists and Darwinists is over the evidence for these intermediate islands/forms. For the Darwinists, these intermediates must exist because Darwinism requires a gradual form of evolution. For the design theorists it’s not that these intermediates can’t exist but that they might not exist and if they don’t, that argues for intelligent design.

In this very brief recap over how design inferences can apply to biological evolution, I’m not laying any blame. The Darwinists are doing what they must to preserve their theory. Insofar as the design theorists argue that the second slide is the one that captures biological reality, the Darwinist may respond that it’s more likely that we haven’t yet discovered the intermediate stepping stones and so really the first slide is the one that applies. The challenge for the design theorist is therefore to marshal clear evidence of cases where we have good reason to think that these stepping stones don’t exist. Often this means looking at irreducibly and minimally complex biological structures and arguing for their unevolvability by Darwinian means. Douglas Axe’s work is perhaps the best in this regard.

Everything I’ve written to this point is stage setting. Darwinists are not attempting to cover up design inference. Instead, they don’t see biology as warranting design inferences, so as far as they’re concerned there are no design inferences to be legitimately made for biology. The situation, however, is quite be different when someone knows that an event, object, or structure is the product of design but wants to hide that fact. A design inference may be warranted and even compelling, but a cover-up is desired to obscure it.

So how do you cover up a design inference? Reports about efforts of the Chinese government to deny that the coronavirus originated in a Wuhan lab (that would be design) exemplify how this might be done or at least attempted. Just to be clear, I’m not a conspiracy theorist and I haven’t looked closely at the evidence for the coronavirus exhibiting telltale markers in its structure that would warrant a design inference. I don’t know. And I’ve got a day job as a businessman, so I’m not going to spend a lot of time to figure this out.

My interest here is simply in the logic of covering up design inferences and how the reports (rumors) I’m hearing about China trying to cover up a design inference vis-a-vis the human origin of the coronavirus may illustrate that logic. Briefly, what I’m seeing is a pre-theoretic design inference without laying out the full specifications and (im)probabilities that must be made explicit in any full-fledged inference of this sort. Thus, in yesterday’s Wall Street Journal, medical doctor Stephen Quay and Berkeley physics professor Richard Muller write:

The possibility that the pandemic began with an escape from the Wuhan Institute of Virology is attracting fresh attention… [T]he most compelling reason to favor the lab leak hypothesis is firmly based in science. In particular, consider the genetic fingerprint of CoV-2, the novel coronavirus responsible for the disease Covid-19. In gain-of-function research, a microbiologist can increase the lethality of a coronavirus enormously by splicing a special sequence into its genome at a prime location… [I]n the entire class of coronaviruses that includes CoV-2, the CGG-CGG combination has never been found naturally. That means the common method of viruses picking up new skills, called recombination, cannot operate here. A virus simply cannot pick up a sequence from another virus if that sequence isn’t present in any other virus… Although the double CGG is suppressed naturally, the opposite is true in laboratory work… Now the damning fact. It was this exact sequence that appears in CoV-2. Proponents of zoonotic origin must explain why the novel coronavirus, when it mutated or recombined, happened to pick its least favorite combination, the double CGG. Why did it replicate the choice the lab’s gain-of-function researchers would have made?

If this is not a full design inference in the sense of my Cambridge University Press monograph, it’s close. Obviously, the Chinese government wants to forestall this inference, keeping it not only from becoming widely known but also from seeming to be plausible or worse yet convincing. So how does one render a design inference implausible even when design is actually the operative cause? In other words, how does one cover up a design inference?

What the Chinese government is or may be doing here has yet to display a smoking gun, but what’s important for my purposes here is the underlying logic—in other words, what the Chinese government might be doing and how its actions might help them to cover up a design inference that would make them look bad. For instance, Adam Housely has tweeted “China is trying to produce variants that suggest it came from bats to cover up that coronavirus originally came from a lab.”

So the strategy for covering up design seems to be to create more designed things like it and then ascribe them to natural forces so that the original thing for which a design inference produced discomfort gently vanishes by being blended with other things that are in fact designed but can more readily be made to appear as natural and thus as undesigned.

The logic here has all the appeal of a liar trying to hide a lie by multiplying other lies. But that’s not to say it can’t be effective if effectively pulled off. In the case at hand, one takes the coronavirus that caused the worldwide pandemic and that is the subject of a design inference and one then camoulflages it with multiple variants that are, in fact, likewise designed, but that can be slipped into bat and other animal populations, thus made to appear that they arose naturally. And if they can appear to have arisen naturally, then why not the original coronavirus that infected humans and is the main point of concern?

The logic then takes the form of the two slides that I used to show in my design talks, but with the order reversed. The slide without intermediates, namely,

is the one that seems to capture what’s really going on, and thus suggests a design inference for the far off island. But then, to forestall the design inference that seems warranted, design and build intermediate stepping stone islands as in the other slide:

The irony here is rich. Indeed, everything in both slides ends up being designed. But the design is less palpable when the stepping stones are present. And since we’re less likely to infer design for them, we’re less likely to infer design for the original island (or in this case the original coronavirus) that initially drew our suspicion and led us to draw a design inference, at least so the cover-up artist (China in this case) hopes. After all, since the intermediates (variant coronaviruses) seem natural, they must not be that improbable, and so no design inference would be warranted since such inferences depend crucially on improbability. In consequence, the object that initially drew our suspicion is likewise released from a design inference.

How then to cover up a design inference? Essentially, one doubles down on design in order to repudiate design. Thus one intentionally generates designs that are less likely to seem designed, thereby camouflaging the very thing whose design one is most concerned in denying. This seems the preferred way to cover up the design inference, at least for now in the case of the coronavirus.